Today marks the anniversary of the deportation of the Chechens by Stalin in 1944. On this occasion we publish an excerpt from the first volume of “Freedom or Death!” History of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria

Operation Lentil

While Israilov fought his little war against the USSR in Chechnya, the world was facing the tragedy of World War II. In June 1941, Axis forces invaded Russia and were stopped at the gates of Moscow. In the summer of the following year, Hitler directed his sights on the Caucasus, trying to cut Stalin the oil supplies needed to move his armored divisions. The German avant-gardes reached the town of Malgobek, in the extreme west of the Chechen – Inguscia RSSA. Israilov issued an “appeal to the people” in which he invited the population to welcome the invaders as allies if they saw favorably the independence of the Caucasian peoples. For their part, the Germans tried to encourage the insurrection, in order to weaken the already tried Soviet defenses,[1]. However, there were contacts with the rebels, and Israilov seemed willing to collaborate with the new occupiers, making his men available against the anti-Nazi partisan resistance, in exchange for the promise of independence.

In February 1943, following the devastating defeat at Stalingrad, the Wehrmacht withdrew from the Caucasus, abandoning the Chechen rebels to their fate. Stalin’s reaction was merciless. Towards the end of 1943, when Chechnya had returned to being the rear of the front, the Soviet dictator ordered the Minister of the Interior, Lavrentji Beria to deal once and for all with that turbulent people who, in the most difficult moment of the war, had not contributed adequately to the war effort of the USSR[2]. The question of the lack of loyalty shown by the Vaynakhs during the war was not very consistent, but it was also an excellent ideological umbrella to cover an “Ermolov-like” solution to the Caucasian problem at a time when the world was not interested in looking at what was happening in that corner of Europe.

Beria carried out Stalin’s order with cynical professionalism: after bringing a brigade of NKVD agents to Grozny[3], ordered his men to collect evidence of the “betrayal” of the Chechens and their neighbors Ingush. The final report drawn up by the People’s Commissars cited the presence of thirty-eight active religious sects, with about twenty thousand adherents, whose purpose was to overthrow the Soviet Union. Stalin’s relentless executioner had already cut his teeth as a persecutor first in his native Transcaucasia (where he had administered the purges) then in Poland, and in the Baltic countries (where he had completed the purge of intellectuals and bourgeois) thus, after putting his military machine to the test by completing two “small” ethnic cleanings in Kabardino – Balkaria and in Karachai – Circassia, he decided to develop that of the Chechens for the end of winter.

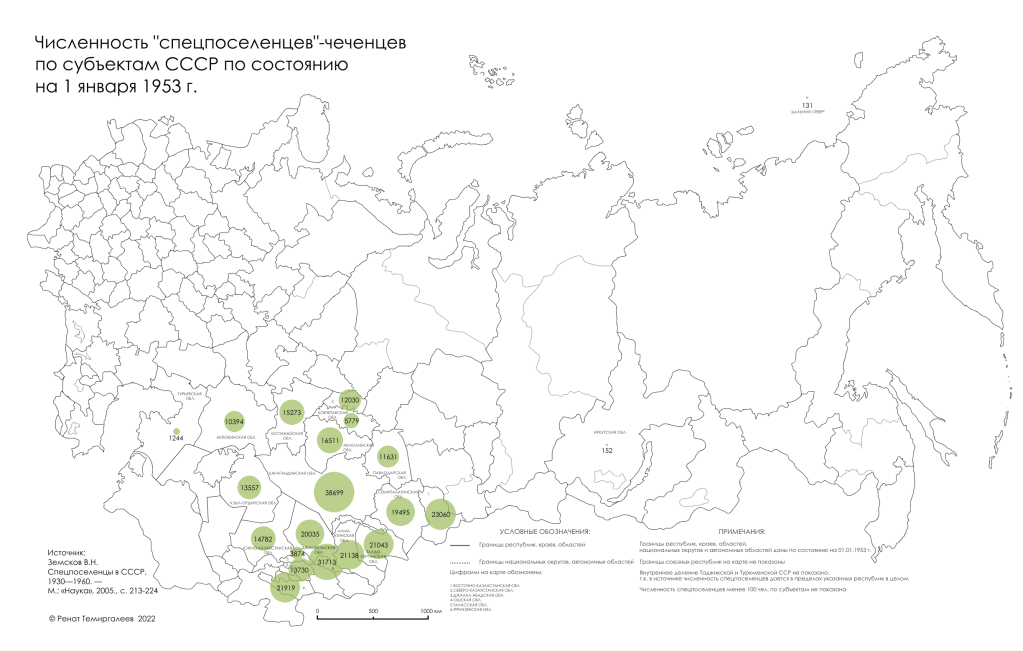

Between December 1943 and January 1944, one hundred and twenty thousand men between soldiers and NKVD officials were stationed in Chechnya, officially to support the reconstruction and prepare the harvest. Transport vehicles and freight trains were herded in military warehouses and railway stations, while soldiers set up garrisons across the country. In the night between 22 and 23 February, the so-called Operation Lentil began, which went down in history with the Russian term of Chechevitza and the Chechen term of Ardakhar: within a day three quarters of the entire Chechen people – Ingush were loaded onto trains goods and shipped to Central Asia. In the following days the same fate struck the last quarter. Anyone unable to move or resisting was executed on the spot.

Any resistance was useless. The villages in which they occurred were set on fire, and their inhabitants slaughtered. In the south of the country, where the snow was still deep and travel difficult, communists did not have too many problems forcing the populations to march in the snow to reach their destinations. The elderly, children and the disabled ended up shot or abandoned to their fate[4]. For those who got to the trains alive, a three-week death journey began. Crammed beyond belief in leaded wagons with no toilets, they set out on a three-thousand-kilometer journey across the snowy steppe, surviving on what little they had managed to take with them.[5]. Between 10 and 20% of the deportees died during the crossing. The survivors were dumped in bulk and forced to build themselves shelters and huts on the fringes of collective farms for which they would be the lowest form of labor. The Soviet government imposed compulsory stay on them. Every month the exiles would have had to report to the authorities and declare their presence, on pain of a 20-year sentence of forced labor.

Nothing remained of the Chechen – Ingushetia: the republic was dissolved, its districts were annexed to neighboring republics or transformed into Oblast, provinces without identity. All the cultural heritage of the Chechens was destroyed: mosques and Islamic centers were demolished, and their stones became building material. Even the stems that adorned the cemeteries were removed and used for the construction of houses, government buildings, even stables and pigsties. The tyaptari, the teip chronicles written on parchment and preserved by the elders, were burned or transferred to the Moscow archives. The depopulated country was filled with war refugees. From the regions most devastated by the conflict, hundreds of thousands of Russians were placed in a Grozny, which has now become a ghost town. Only a handful of survivors, who remained in Chechnya by chance or because they escaped their tormentors, continued to live in hiding in the Mountains. Israilov himself managed to escape arrest until December 24, 1944, when he was identified by the police and killed in a shooting. For all the others, an ordeal began that would last thirteen years, until Stalin’s death.

The deportees had to face the terrible conditions of nullity among populations who barely had to feed themselves. The death rate from disease and malnutrition soon reached dramatic levels. In the three-year period 1944 – 1947 alone, one hundred and fifty thousand people died, about a quarter of the population. The survivors lived in collective lodgings in which up to fifteen families were accommodated, mostly without stable employment and without resources. Those without a job wandered across the steppe in search of animal carcasses, or wild herbs, or tried to steal food from collective farms. Anyone who managed to get a job in one of these could hope to make ends meet:[6].

On hopes that the exile was a temporary punitive measure, and that sooner or later the central government would consider their guilt extinguished, the Supreme Soviet came to put a tombstone. In a special decree it was established that

In order to determine the accommodation regime for deported populations […] it is to be considered perpetual, with no right of return […].

The Chechens were forced to sign the decree one by one.

The sons of Ardakhar

Deprived of their land and their customs, the Chechens tried to preserve their identity by handing down their stories orally and entrusting themselves to the elderly, who in the absence of anything else had become the only custodians of shared memory. Thanks to the traditions transmitted from generation to generation, Adat and Islam were kept alive in the uses and customs. The Soviet government tried to eradicate both, opening schools of ideological education and infiltrating the KGB among the Islamic communities, but the national sentiment of the Chechens did not fail and indeed strengthened in the resistance to the emancipation programs launched by the authorities. The distance from the homeland and the lack of written sources produced a simplified, idealized and mythologizing story, which would become the creed of that generation that would reach maturity in the early 1990s[7].

Among the hundreds of thousands of deportees who suffered the sad fate of exile was a child named Dzhokhar. He was born on February 15, 1944, nine days before Stalin ordered the deportation of all his people. Thirteenth son of Musa Dudaev, veterinarian, and his second wife Rabiat, he lived his childhood in a pariah community, considered unworthy to participate in the great socialist project, marginalized and closed in on itself. When his father died, leaving behind a large and resourceless family, his mother was allowed to move to the city of Shymkent in southern Kazakhstan, where the climate was milder and there was greater demand for labor. Dzhokhar, who had taken the dedication to study from his father, managed to complete primary school with merit[8]. With no higher education institutions available, he tried to support the family by working where possible, to bring home something that could alleviate his mother’s fatigue. It was in this situation that the news of Stalin’s death caught him. It was March 5, 1953, and the Chechens had been in exile for nine years.

The new Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev, launched a series of measures aimed at softening the iron fist with which the regime had governed the USSR in recent decades, which in the following years would take the name of De-Stalinization. The first step was to get rid of Stalin’s loyalists, starting with the hateful Beria, who was tried and put to the wall within a few months to the delight of the Chechens and all the other deported peoples. The second was to forgive the enemies of the state that the tyrant had persecuted. From 1954, therefore, the status of special settler was revoked for all Chechens under the age of sixteen, allowing them for the first time to move from their forced home to work and study. In August 1955 this freedom was also recognized to teachers, to war decorated, to women married with Russians and to invalids. For all others the restrictions persisted, but the penalty for abusive abandonment of the settlements was reduced from 20 to 5 years of forced labor. The number of convictions dropped significantly, going from eight thousand in 1949 to just twenty-five in 1954.

Finally, on July 16, 1956, the long night of Ardakhar officially ended. By decree of the Supreme Soviet, the ban on returning to the lands of origin was officially lifted. On January 9 of the following year the Chechen – Ingush RSSA was re-established, to which all the districts that made it up were re-annexed except for one, that of Prigorodny, on the border with North Ossetia.

The Soviet government, aware that a mass return of Chechens would create many problems, tried to govern the phenomenon by setting up a sort of waiting list that would stagger the resettlement, but the impatience of Chechens and Ingushes to return to their homes was not negotiable and already in 1957, in the face of 17,000 authorizations, at least fifty thousand people returned home. During 1958 the exodus became torrential, with the return of 340,000 deportees, mostly without employment, education and economic resources, and by 1959 83% of the Chechens and 72% of the Ingush were on a permanent basis within the ancient borders. Local governments were unable to handle such a massive influx of people, and district governors asked Moscow for help.[9].

The ancient inhabitants of Chechen – Ingushetia turned into “immigrants in their own homes”, ending up occupying the lowest positions of a social pyramid at the top of which were the Russians, to whom Stalin had given their houses and lands. This situation soon produced a sort of “apartheid” between the Russians, who held the monopoly of industry and administration, and the Chechens, who made up most of the agricultural labor or, at worst, were unemployed, forced to do seasonal work. underpaid and without protections[10]. It didn’t take long before the friction between the two peoples escalated into violence: on August 23, 1958, an Ingush killed a Russian in a brawl. It was the spark that ignited an anti – Chechen pogrom during which dozens of people were lynched, some public buildings were set on fire and that only the intervention of the army was able to quell.

Obviously not all Russians opposed the integration of the Chechens. Many residents made some plots of their private land available to the new arrivals, and in the schools the teachers’ efforts in the preparation of the young Chechens were great and selfless. The central government promoted the image of a Chechen – Ingushetia where cultural differences were respected and where different ethnic groups collaborated in the realization of socialism in peace and harmony. For this to be effectively achieved by Moscow, huge economic resources began to arrive for the construction of housing, schools, cultural centers and health services. In short, the budget of the Chechen-Ingush RSSA became dependent on the generous donations of Moscow, which came to represent even 80% of the public budget, triggering a phenomenon of financial dependence which, as we will see, would have given its bitter fruits thirty years later.

[1] Operation Schamil – Planned and implemented between August and September 1942, it involved sending small groups of commandos and saboteurs beyond the front lines. Their goal was to protect the oil infrastructure from planned destruction by the Red Army in the event of a withdrawal from Chechnya. In the summer of 1942 five groups of raiders, totaling 57 men, were parachuted over the front line. Some made contact with Israilov’s anti-Soviet resistance, others occupied the refineries, assuming a defensive position pending the arrival of the German armored divisions. The failure of the summer offensive in the Caucasus and the formidable defense offered by the Russians in Stalingrad prevented the Axis units from advancing to Grozny.

[2] Stalin’s judgment did not take into consideration the sacrifice of tens of thousands of Caucasians in the battles that the Red Army had fought against the Germans: Chechens had been the first fallen of the Soviet army, heroically defended the position in the siege of Brest. Chechen was Khanpasha Nuradilov, a very skilled sniper during the Battle of Stalingrad and also Chechens would have been Movlad Bisaitov, the first soldier to meet the allies on the Elbe River and Hakim Ismailov, who together with his team was the one who hoisted the red flag on the ruins of the Reichstag. Over the course of the conflict, more than 1000 Chechens would be rewarded for their fighting actions.

[3] NKVD – Narodnyj komissariat vnutrennich del (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs) was the organization responsible for state security during the Soviet period. Born from the ashes of the Tsarist imperial police, he took control of both detention facilities and branches of the police, including the notorious political police. The NKVD was the armed arm of Stalin’s policy of terror. In 1946 the organization was transformed into the Ministry of Internal Affairs, while its political police section was renamed the State Security Committee, known as the KGB.

[4] Particularly bloody was a massacre that many Chechens still remember today. In the village of Khaibakh, in the mountainous Galanchozh district, snow prevented any movement. But Beria’s orders were clear and rather than disappoint his superior, the NKVD officer operating in the area, Colonel Gveshiani, ordered the elimination of anyone unable to cope with the march. Hundreds of people were gathered in a barn, where they were executed.

[5] In a report to “Comrade Stalin” Beria wrote: Between 23 and 29 February 478,479 people, including 91,259 Ingush, were concentrated and loaded onto trains. 177 trains have been filled, 152 of these have already been sent to the resettlement sites. […] 6,000 Chechens from the Galanchozh district still remain not. rearranged due to heavy snow and the impracticability of the roads. However, their removal will be completed in the next two days […] During the operation 1016 anti-Soviet elements were arrested. A few days later, in a second report, Beria reported that at the end of Operation Lentil, 650,000 people had been “successfully” deported.

[6]In addition to food, there was a lack of clothes. In January 1945 the assistant to the President of the Assembly of People’s Commissars wrote in his report: The situation of the clothes and shoes of the special settlers has completely deteriorated. Even without taking into account all those who are unable to work, children are practically naked, and as a result disease causes high mortality rates. The absence of clothing prevents many of the healthy young people from being used in agricultural activities.

[7] As historians Carlotta Gall and Thomas de Waal have noted: The experience of deportation was a collective experience based on ethnic criteria […] Thirteen years of exile undoubtedly gave the Chechens, for the first time, the sense of a common identity. The proximity of the Chechens in the deportation has become legendary for themselves.

[8] Considering the fact that in those years only sixteen thousand Chechen children out of fifty thousand had access to some form of basic education, Dzhokhar Dudaev could say he was lucky to have had the opportunity to study.

[9]Even in 1958, one year after Khrushchev’s “forgiveness”, only a fifth of Chechens had managed to obtain a home. For the others, makeshift lodgings remained in industrial complexes, in dilapidated huts or in the ruins of ancient farms on the plateaus and mountains. Even at the employment level, the situation remained critical for a long time: due to low schooling, most Chechens did not possess the necessary qualifications to obtain the best jobs in the country’s factories and refineries, and the distrust with which local managers, all ethnic Russians, they looked at them made integration even more difficult. The school gap was very high: in 1959, compared to 8696 skilled workers of Russian origin, there were 177 Chechens occupying the same position,

[10] The reader who wants to deepen the question of the Chechen economic system – Ingush in the Soviet period can find two detailed insights on the blog www.ichkeria.net entitled The agricultural economy of ChRI.