The following is a preview of the second volume of “Freedom or Death!” just released in English. The passage deals with Russian and Chechen preparations in the days immediately preceding the outbreak of war.

Zero Hour

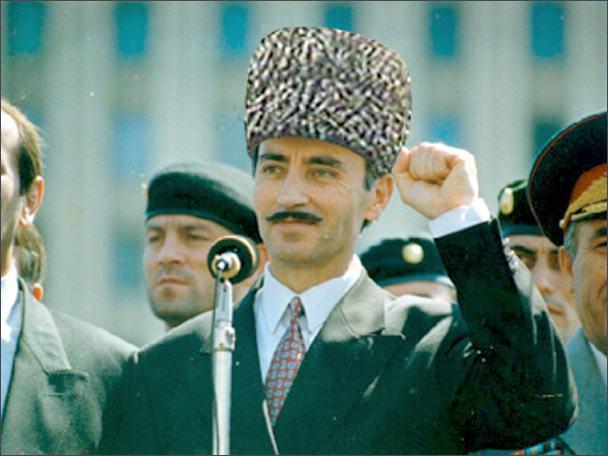

In 1994, Russian-backed forces in Chechnya opposing Dzhokhar Dudayev led the failed November Assault, and it was a moment of realization for everyone.[1] President Yeltsin now clearly understood he needed to do more than covertly support groups inside Chechnya. He had to officially intervene to prevent the small, historically rebellious mountain republic from seceding. The Chechen opposition’s Provisional Council itself desperately appealed to him to send troops against the Dudayevites.[2] Meanwhile, General Dudayev was hopeful for peace negotiations but took seriously the threat of Russia fully invading.

For Yeltsin and Defense Minister Pavel Grachev, victory was not an achievable objective but a ripening fact. A “small victorious war” promised to raise the administration’s ratings against the increasing popularity of nationalist parties.[3] They ignored, or pretended to ignore, the deplorable state of their military and underestimated their enemy’s determination. Meanwhile the Chechens were preparing to resist the invasion.[4] Dudayev entrusted command of the regular forces to Colonel Aslan Maskhadov,[5] who inherited ragtag units rather than an army from his former colleague Viskhan Shakhabov.[6] Throughout 1994, he attempted to structure it partly according to army reforms enacted in 1992 and based on pre-existing forces, which were comprised of veterans from wars in Afghanistan and Abkhazia. Some units were combat-ready by the beginning of December. Among such forces was the Presidential Guard commanded by Abu Arsanukaev, and its Spetnatz unit under Apti Takhaev. Next was Shamil Basayev’s Reconnaissance and Sabotage Battalion, which was composed mostly of veterans of Abkhazia. Then came Ruslan Gelayev’s Special Borz (“Wolf”) Regiment, which included a battalion led by Umalt Dashayev. Adding also the Shali Armored Regiment and other minor units, there was a nucleus of 1,500 troops joined by 1,000 men from the Ministry of the Interior and the National Security Service (police officials, riot police and state intelligence services). Maskhadov added some volunteer territorial militia battalions, such as the so-called “Islamic Regiment” under Islam Halimov and the Naursk Battalion[7] with Major Apti Batalov.[8] Thanks to their contribution and the many other bands of volunteers who rushed to Grozny’s defense, Chechen Headquarters relied on 5,000 men at the start of Russia’s invasion. Several more formations followed Dudayev’s general mobilization proclamation on 4 December.[9] The Chechens understood however, that regardless of how they prepared they could only temporarily hold the enemy at the gates. Chechnya lacked the numbers, arms, and organization to take on enemy armored brigades directly.[10] Russia had even preemptively destroyed the modest air force on 1 December.

Russia’s initial approach to the invasion reflected its narrow aim to eliminate the leadership rather than destroy Chechnya. The average Russian solider, struggling to pin it on a map, cared even less about Chechnya. The government narrowed its invasion partly to avoid a humanitarian crisis since the wary West was watching with a hand on the money tap keeping Russia afloat.

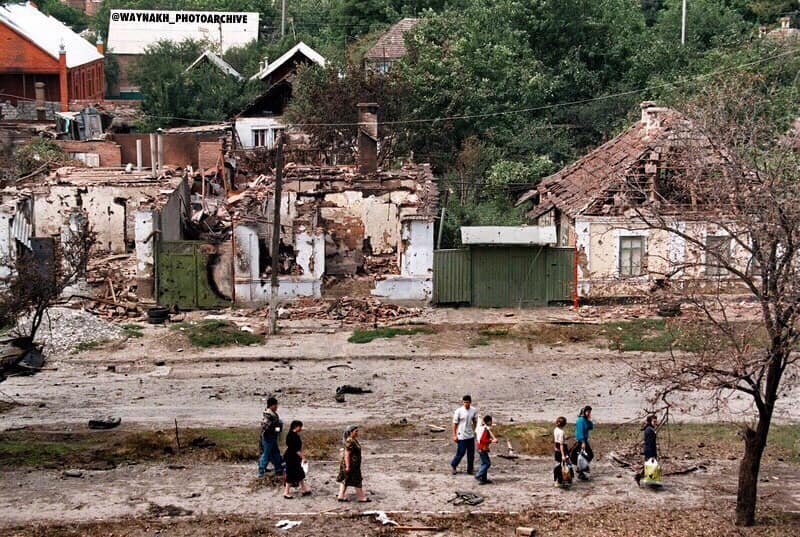

Whatever way the Russians intended to attack, the Chechens were preparing to fight and die all the same. Their plan was “to last.” They wanted to resist as long as possible and hopefully expose the Kremlin to domestic public opinion, which was still struggling with trauma from the Soviet-Afghan War. Equally important was the opinion of the West, whose conditional loans kept Russia’s economy from sinking.[11] The Chechens organized their defense in three phases. They planned to first trap the Russians inside Grozny, a “concrete forest,” and ensnarl their overwhelming armor. To entice the Russians, the Chechens yielded the defensive line to the north to create the illusion they had abandoned the capital. This line along a strip of hills running north of Grozny on the so-called Terek Ridge hinged to the west by the villages Dolinskyand Pervomaisk. It ended in the east at the height of the village Petropavlovskaya on the left bank of the Sunzha. After crossing the line and penetrating the capital, the Russians would encounter Chechnya’s best forces eagerly waiting to recreate the success they had against the anti-Dudayevites back in 26 November. This was ideally going to force Yeltsin to negotiate with Dudayev, but with far more realistic expectations, the Chechens planned to retreat south to the main centers of Achkhoy-Martan, Shatoy, Vedeno, and Nozhay Yurt.

Maskhadov divided the territory into six military districts called “Fronts” and entrusted them to his best men.[12] The loyal former police captain Vakha Arsanov held the Terek Ridge Line. Ruslan Gelayev was charged with the South-Western Front, a quadrilateral defined by the villages Assinovskaya, Novy-Sharoy, Achkhoy-Martan, and Bamut. Dudayev’s twenty-eight-year-old son-in-law Salman Raduyevcommanded the North-Eastern Front centering on the city Gudermes. CommanderRuslan Alikhadziyev[13] of the newly appointed Shali Armored Regimentled the southern front, with its main centers being Shatoyand Shali. Turpal Atgeriyev, a twenty-six-year-old veteran of the Abkhaz War and one of Raduyev’s most trusted men led the South-Eastern Front, centering on Nozhay Yurt. Finally, Shamil Basayev held Grozny. Unfortunately, the government lacked a comprehensive plan to protect the population,[14] and the situation was especially dire in Grozny. Unlike their Chechen neighbors there, the many ethnic Russian residents did not have relatives and friends in the countryside to flee to.

The Russian Headquarters was busily gathering nineteen thousand fresh conscripts from the most diverse branches. Collectively baptized the “Joint Group of the United Forces,”[15] it also included five thousand soldiers from the Interior Ministry to comb the rear for enemies. The army was divided into the West, East, and North groups.[16] West Group started off from Vladikavkaz, North Ossetia to penetrate in three columns, taking up a position at the height of Novy-Sharoy behind the Chechen Terek RidgeLine. From Klizyar, Dagestan, East Group was to reach Tolstoy-Yurt along the Terek River. Finally, North Group in Mozdok, North Ossetia would cross the pro-Russian occupied plains of northern Chechnya to link up with East Group north of Grozny. With one hundred kilometers to the objectives, the operation had a schedule of a couple days. The high command of the Russian military prepared to issue an ultimatum to the leadership and offer amnesty to Chechen troops who surrendered.[17] Afterwards, artillery would clear the way for tanks to finally crush the rest of Dudayev’s “little rebellion”.

However, the commander of the Russian operation Colonel General Eduard Vorobyov refused to lead the plan,[18] dismissing it as “madness”and a dishonor to send the military against citizens Russian considered its own.[19] Grachev promptly dismissed and investigated him, and instead tapped the unquestioning General Anatoly Kvashnin. Vorobyov’s forced resignation quickly led to the replacement of the Military Command of the Caucasus, further disrupting the chain of command which, on the eve of the invasion, was completely “purged.”

There were also important fringes of Parliament, including in the majority, opposed to military intervention. Yegor Gaidar, one of Yeltsin’s closest allies and chairman of the pro-government Democratic Choice of Russia Party,[20] spoke out and brought others from his faction with him.[21] Galina Starovoytova from the Democratic Russia Party was also opposed. Many moderates remained ambivalent though: the newly established center-left Yabloko Party saw heated internal debate between skeptics and those that supported the invasion “in principle” if not in execution.[22] On the right, nationalist movements beat the war drums, particularly Vadim Zhirinovsky’s Liberal Democratic Party. Opponents argued that using the military was unconstitutional without the government declaring a state of emergency and imposing martial law. According to Article 102 of the Constitution, the president had to consult Parliament to issue the provision, which would likely have been rejected. Supporters of military action, on the other hand, pointed to Articles 80 and 86 as support for Yeltsin’s right to lead the military and his duty to “safeguard the sovereignty” and “integrity of the state.”[23] A public debate could perhaps have steered tanks away from the Caucasus, especially as concerned newspapers all over the world began to cover the matter.[24] But the die was cast, and Yelstin was moving his pieces towards Chechnya.

[1] For more on the November Assault and the events preceding the outbreak of the First Russo-Chechen War, see Volume I of this work.

[2] In a conversation with the author, Ilyas Akhmadov recalled a telegram from the Provisional Council explicitly requesting Yeltsin to intervene. It was signed by Umar Avturkhanov and arrived in Moscow in the first days of December 1994.

[3] One analysis of the beginning of Yeltsin’s political shift: “With the controversial decision to use force to stop the secession of a small ‘province’ of his empire, Yeltsin himself also crossed a political ‘Rubicon,’ from which it will be difficult to go back: that of the alliance with the democratic forces that had supported him from the dissolution of the USSR in 1991 to the bloody battle against the rebel parliament in ’93. . . . After the victory of nationalists and communists in the legislative elections of December ’93, Yeltsin assumed new positions in foreign policy and in the management of economic reforms, thus trying to pander to the opposition, regain popular consent, and maintain power at the next electoral appointments, the legislative ones in a year, the presidential elections in a year and a half.” (Enrico Franceschini, “A Peace Party in Moscow,” La Repubblica, December 19, 1994).

[4] Chechen Foreign Minister Shamsouddin Youssef responded to news of Russia’s likely invasion by demanding Russia to recognize Chechnya’s independence. Otherwise, the Chechens would “fight, and bring war in the Russian Federation.” On the same day, Aslan Maskhadov added that Moscow risked fighting a “new Afghanistan.” First Name Last Name, “Title,” La Repubblica, May 12, 1994.

[5]Aslan Alievich Maskhadov, introduced in Volume I of this work, was born in Shakai, Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic, and returned to Chechnya with his family in 1957. He enrolled at the Artillery School of Tbilisi in 1972, then perfected himself at the High School of Kalinin Artillery in Leningrad. After his service in Hungary, he transferred to Vilnius and witnessed the Lithuanian independence uprisings. After resigning in 1992, he returned to Chechnya again and entered Dudayev’s service. In November 1993, he replaced Viskhan Sakhabov as chief of the general staff, first on an interim basis, then permanently beginning in March 1994. For a comprehensive biography written by his son Anzor, see Frihetskjemperen: Min far, Tsjetsjenias president.

[6] As Musa Temishev shared in a conversation with the author, Viskhan Shakhabov (extensively discussed in Volume I of this work) could not organize the nascent Chechen armed forces as a result of frictions with President Dudayev that arose between 1992 and 1993. Their disagreements on the methods of acquisition and use of Soviet arsenals paralyzed the Ministry of Defense, which was never officially established, leading to Shakhabov’s resignation.

[7] To be precise, Aslan Maskhadov christened the unit “Naursk Battalion” only in January 1995, during a live television broadcast on the presidential channel. The nom de guerre was a eulogy to Batalov’s units who had fought during the siege of Grozny. According to the commander, the regiment was still a “people’s militia”until the Battle for Grozny: “There were no cadres, there were no officers, there were only groups of people from different villages, commanded by people elected by them, totally on a voluntary basis. People came and went, and no one could order anything from them.”To read more about Apti Batalov and the Naursk Battalion, see the series of articles The General of Naur: Memoirs of Apti Batalov at www.ichkeria.net.

[8] Apti Batalov Aldamovich, born in Kyrgyzstan on October 19, 1956, returned to Chechnya and graduated from the Petroleum Institute of Grozny as a civil engineer. After entering the police force, he served as part of the Ishcherskaya Militia in the Naursk district, becoming its commander on June 20 1994. According to our conversations, until early August he served under District Military Commander Duta Muzaev, Dudayev’s son-in-law. After Muzaev’s return to Gronzy, Batalov became of head of the military administration of the Naursk and Nadterechny districts on September 16, 1994. He was tasked with organizing their defense against raids by the pro-Russia armed opposition.

[9] On 4 December, President Dudayev proclaimed a total mobilization of reservists. All male citizens between the ages of 15 and 60 were summoned, too many to realistically arm and train for the regular forces. Most were sent back to their villages of origin with the task of setting up self-defense militias using light weapons or resorting to hunting weapons.

Regarding the composition and nature of these militias, Ilyas Akhmadov recalled in a conversation with the author in 2022: “During the war there were many local volunteer groups consisting of five or six people, sometimes related to each other. It was very important to find a band that you knew. If you were with someone from your village, street, block, or family, you had a 90% guarantee that they wouldn’t leave your body if killed or injured. If they didn’t know you, they didn’t want you. This was mutually understandable to all: If something happened they would not be able to find the relatives, and for us it was very important to be returned to our families.”

[10] To learn more about the ChRI Air Force and its eventual destruction by Russia, see the in-depth study Green Wolf Stars: the ChRI Air Force on the website www.ichkria.net and consult Volume I of this work.

[11] United States Congress opened debates on 11 December 1994, on financially leveraging Russia to discourage war. Senators John McCain and Joseph Lieberan asked for aid to be reevaluated. Their colleague Alfonse D’Amato, argued on 3 January, that this could “send the wrong signal,”although he felt it necessary to express US displeasure at the civilian losses caused by the invasion.

[12] To view the Chechen defense plan, see thematic map A.

[13] Ruslan Alikhadzhiev was born in 1961 in Shali. After completing his military service with the rank of Sergeant, he returned to Chechnya in 1992. He took command of the Shali Armored Regiment in the autumn of 1994, replacing Isa Dalkhaev. At the outbreak of hostilities he organized the recruitment of militia in the Shali district (the “Shali Regiment”).

[14] Anatol Lieven’s first-hand account: “A government plan to feed the population and evacuate the children if the Russians started a siege? I don’t know of any such thing, but if President Dudayev said so, of course it is true,” an official told me in early December 1994, sitting in his deserted office in the municipal offices of the central district of Grozny, . . . “Anyway, it doesn’t matter. We Chechens are such strong people, we will be able to feed ourselves no matter what happens. Is it my responsibility? What do you mean by this? I’m here in my office, right? Don’t you think I will fight to the death to defend my country?” With that he let out a gasp, blowing a breath of vodka in our direction, and with wet fingers lifted a piece of greyish meat from a glass jar on his knees, and fed it to his cat.” Anatol Lieven, Chechnya: Tombstone of Russian Power (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 34.

[15] The unpreparedness of the federal forces was well known to the military commands, and to the Minister of Defense himself. A few days before the start of the military campaign, Grachev read a top secret directive (No. D-0010) which described “unpreparedness for action of fighting.” Stazys Knezys and Romana Sedlickas, The War in Chechnya, (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1999).

The assessment report drawn up by the office of the North Caucasus Military Region was similar: “Most of the officers are not only unfamiliar with the required combat readiness requirements set out in the control documents, but also do not know how to recognize their personal duties, or what they should do in times of peace or war. Watch officers and units, in most formations inspected, are poorly trained to take practical actions in response to combat commands. The instructions and other control documents are prepared in gross violation of the requirements of the General Staff.” Knezys and Sedlickas, War in Chechnya.

[16] To view the Russian invasion plan, see thematic map B.

[17] The Duma approved a resolution to this effect 13 December 1994.

[18] Grachev’s plan was entirely based on the assumption that a massive deployment of forces would disperse the separatists: “Grachev’s plan and timetable reflect expectations of limited resistance. Little intelligence used and bad planning were to blame… The planning also ignored the experience of loyalist Chechen forces [i.e. thread . Russians] who had attempted to storm Grozny in August , October and November 1994. If that experience had been studied, the Russian command would have been aware of the dangers that faced tank columns in Grozny.”Olga Oliker, Russia’s Chechen wars 1994-2000: Lessons from Urban Combat (Santa Monica: RAND, 2001) 11-12.

[19] As Eduard Vorobjev said in an interview with journalist Vitaly Moiseev: “I was shocked by the situation, the units that arrived were completely unprepared, the commanders did not know their subordinates, many of the fighters did not have the necessary professional skills. I turned to the Chief of the General Staff: ‘If you think that a change of command will change the situation for the better, then you are wrong. It’s not about the commander, it’s about the adventurous approach. . . . Approaching me, the Minister of Defense said ‘I am disappointed in you, Colonel General, and I think you should submit your letter of resignation.’ I replied ‘I have it.’… It was not easy for me, a person who served in the armed forces for 38 years, who constantly answered ‘Yes!’ I was faced with a choice: to make a deal with my conscience and deal with completely unprepared people, to conduct an operation not planned by me, or to leave the armed forces, which meant the end of my military career.… It seems to me that Grachev underestimated the moral and psychological state of the Chechens, which had reached fanaticism. The operation was designed to intimidate: they thought that Dudayev would get scared when he saw hundreds of units and thousands of soldiers, and surrender to the victor’s mercy. Indeed, the Chechen side clearly knew where our troops were, what they were doing—information was spreading in all directions.”

[20] To the press Gaidar declared: “I appeal to Yeltsin not to allow a military escalation in Chechnya. The intervention was a tragic mistake. Taking Grozny will cost huge human losses. It will worsen the internal political situation in Russia, it will be a blow to the integrity of the nation, to our democratic achievements, to everything we have achieved in recent years.” Franceschini, “A Peace Party in Moscow.”

[21] Deputy of Democratic Choice Dimitrij Golkogonov’s response to “Why are you against the invasion?”: “Because my party, Choice of Russia, led by the ex-Prime Minister Gajdar, is against violence, against the use of force to solve political problems. In Chechnya there is a leader, Dudayev, who does not want to lose power, thanks to whom he has enriched himself and his friends with the trade of oil. Independence has nothing to do with it. But to attack Dudayev is to make a criminal a popular hero. . . . A negotiation had to be opened. If Yeltsin had invited the Chechens to Moscow, they would have come running.” Enrico Franceschini, “‘Yeltsin Made Wrong Move in Invading But Remains Leader of Russia,’” La Repubblica, December 15, 1994.

[22] Vladimir Lukin, former ambassador to the United States and prominent member of Yabloko, in his January 24, 1995 speech in the Nezavisimaya Gazeta wrote: “The executive branch has shown itself and society that it can act independently, regardless of and in spite of political pressures . . . In an ideal world, the preposterous and dangerous idea that the military should not be used for internal conflicts should be driven out of the heads of our armed forces. . . . Using the army inside the country in extreme situations, when threats to the state appear, is the norm in democratic states. Nezavisimaya Gazeta.

[23] For careful study of this topic see Stuart Goldman and Jim Nichol, Russian Conflict in Chechnya and Implications for the United States (DC: Congressional Research Service, 1995).See also Victoria A. Malko, The Chechen Wars: Responses in Russia and the United States(Lambert Academic Publishing, 2015).

[24] An example from an Italian newspaper: “In the end, like a mountain annoyed by a daredevil mouse, Yeltsin ordered the direct intervention of his troops. Moscow claims that Chechnya is part of Russia, therefore it is its right to occupy it to restore order. For the moment, Western public opinion seems aligned with this position, considering yesterday’s events as an “internal matter” for Russia: for which there are no international complaints, unlike what happened with the invasion of Afghanistan. But if we look at the substance of the Russian military expedition in Chechnya, some resemblance to the Soviet invasion fifteen years ago emerges. . . . The fact remains that Yeltsin does not hesitate to use tanks when he sees that other means (negotiation, economic pressure, support for the local opposition) do not produce results. The propensity to resolve political crises militarily, as a year ago in the tug of war with the rebel Parliament, is a hallmark of his presidency. The future will tell whether Russia needed a “strongman” to become a civilized and democratic nation”. Enrico Franceschini,“Moscow Fears the Kabul Syndrome,” La Repubblica, December 12, 1994.