On the thirty-second anniversary of Chechen independence, we publish an excerpt from the first volume of “Freedom or Death! History of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria” which retraces the events that led to the dissolution of the Chechen-Ingush Supreme Soviet, and the proclamation of independence.

————–

In early September, the echo of the August Putsch began to fade in Moscow and the main Russian cities, and Yeltsin was able to return to rest his gaze on the turbulent peripheries of the empire. Chechnya had gone into a state of turmoil, but the Russian president did not give too much weight to the alarming reports from the local Supreme Soviet. He was convinced that all that noise was nothing more than an anti-caste regurgitation as had been seen so many at that time in the USSR. He thought that it would be enough to replace Zavgaev with someone else to be able to calm the hearts of the people and restore Chechnya – Ingushetia to social peace. So he thought of Salambek Hadjiev, a professor who had made headlines a few months earlier, when he was appointed Minister of Chemical and Oil Industry of the Soviet government. Born in Kazakhstan, Hadjiev had earned a position in academia, graduating from the Grozny Petroleum Institute and then working on it until he became its director. A prolific researcher, he was a member of the Academy of Sciences, as well as one of the leading experts in the petrochemical sector in all of Russia. Known for being a moderate anti-militarist (he was head of the Committee for Chemical Weapons and Disarmament) he represented in all respects the “mature” alter ego of the leader Dudaev. Yeltsin appreciated him because he could speak to both intellectuals and entrepreneurs, had a modern vision of the state and was a hard worker. He seemed to have all the credentials to compete with the General, who had his nice uniform, good rhetoric and little else on his side. The idea of replacing Zavgaev with Hadjiev also pleased the President of the Supreme Soviet Khasbulatov, who, as we have seen, certainly did not like the current First Secretary. Hadjiev, on the other hand, was a man of high intellectual qualities like him (who was a professor) and like him he had a moderate and reformist vision. Arranging one of “his” people in power in Chechnya would also have been convenient for him in terms of elections, so he worked to ensure that the change took place as soon as possible.

Khasbulatov then headed to Chechnya to secure a painless changing of the guard. His notoriety, now that he was at the top of the Soviet state, his culture and his political ability would have allowed him to oust his hateful rival and to install a viable alternative that averted civil war and favored his position. However, there was to be reckoned with the nationalists, who grew up in the shadow of the crisis and rebelled during the coup.

To vanquish them, Khasbulatov drew up a plan. From his point of view, the nationalists were an amalgam of disillusioned, desperate and opportunists, held together by a vanguard of young idealists unable to rule the beast they were raising. Faced on the terrain of political debate, most likely they would have ended up being reduced to a residual fraction. Only the context, according to him, allowed them to occupy the scene. Despair and lack of alternatives were the ingredients of the mixture that threatened to break out the revolution. To neutralize the threat it was necessary to “change the air”: the opposition had strengthened against Zavgaev and his corrupt regime, getting him out of the way was the first step. There was to replace him with someone who had good numbers. And Hadjiev seemed the right one. The solution, however, he could not descend from above. It was necessary to establish an alternative consensus front to Dudaev and for this it took time. The nationalists had conquered the streets riding the wave of the institutional crisis. Getting them bogged down in a political diatribe by letting time pass, while the situation normalized, would have deprived the Dudaevites (as the supporters of the General began to call themselves) the ground under their feet. As socio-political conditions stabilized, the desperate would be less and less desperate, the disillusioned less and less disillusioned. People would have listened to those who called for calm and reforms rather than revolution and war, and the radicals would be marginalized. Finally, with a good democratic election, the moderates would have won and the revolutionaries would have lost.

A perfect plan, in theory, which, however, was based on two significant variables. The first: that Dudaev and his people were too afraid to force their hand, thus leaving the initiative to him. The second: that the situation in Moscow did not degenerate further. And Khasbulatov, unfortunately for him, could not control either the first or the second. Yet somewhere we had to start and so, from 23 August, the President of the Supreme Soviet went to Grozny, accompanied by Hadjiev, with the intention of killing Zavgaev. In a turbulent meeting of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, to the First Secretary who begged him to authorize the proclamation of a state of emergency and to disperse the opposition, Khasbulatov replied that the use of force was absolutely to be avoided, and that the solution of the crisis should be political, which meant only one thing: resignation.

Having cornered Zavgaev, he went to test his opponent. His first conversation with Dudaev seemed to be promising: the General welcomed him with affability and agreed to his proposal to dissolve the Supreme Soviet and replace it with a provisional administration to ferry the country into the elections. Satisfied, he returned to Moscow convinced that he had brought home a good point. The real goal, however, was achieved by the leader of the nationalists. Discovering Khasbulatov’s cards, he was now clear that no one would raise a finger to defend the legitimate government of Chechnya – Ingushetia: a casus belli would be enough to force the hand and take control of the institutions. Thus, while Moscow was toasting to the happy solution of the crisis, in Grozny the Dudaevites took control of the city and besieged the government, now without an army to defend it. Nevertheless, Zavgaev did not intend to give up. His abdication could only have been imposed by a vote of the Supreme Soviet, and almost none of the deputies had any intention of endorsing it, considering that a moment later the Soviet itself would be dissolved. Thus the situation remained at a standstill for a few days, with the government not resigning and the nationalists not abandoning the streets.

Between 28 and 30 August Dudaev began to test Moscow’s reactions: the National Guard broke into numerous public buildings, occupying them and displacing anyone who opposed them. Not a breath came from Moscow. Then the General ordered the establishment of armed patrols to guard the streets, and once again there was no reaction. Chaos was taking over the country and nobody seemed to care that much[1].

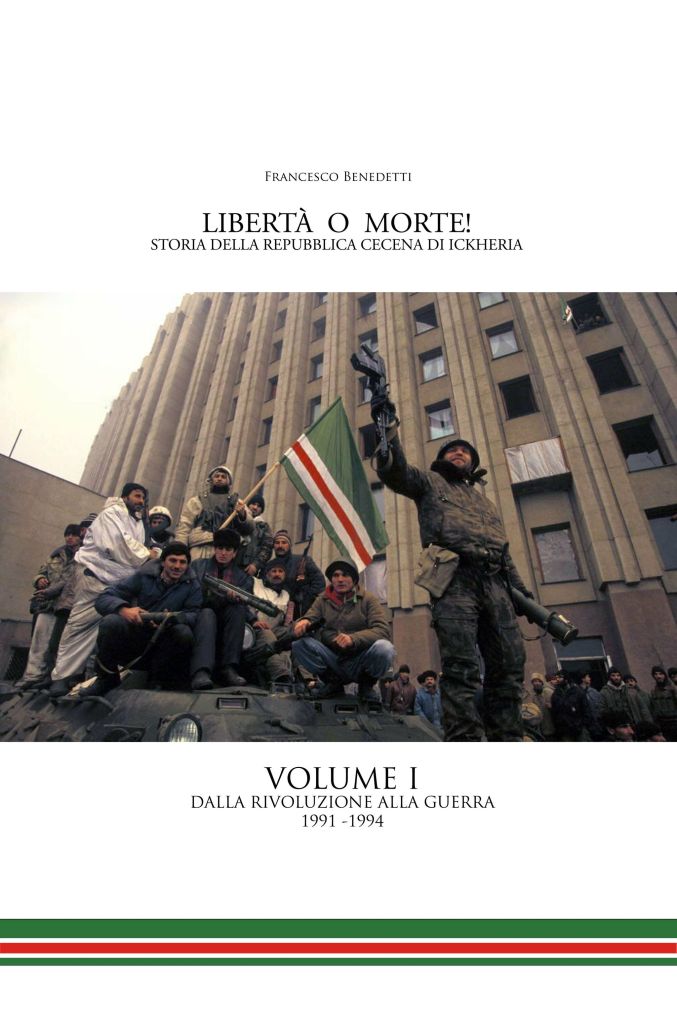

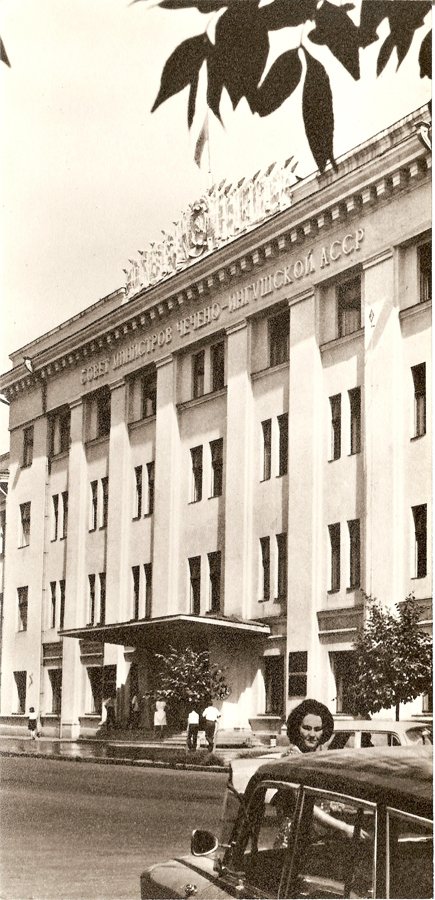

On September 1, Dudaev called the third session of the Congress. The National Guard presided over the assembly. Armed volunteers erected barricades all around. A group of militiamen entered in the Sovmin, occupied it and lowered the flag of the Chechen-Ingush RSSA, hoisting the green banner of Islam in its place. There was no trace of the moderates: ousted in the June session, they were now unable to influence public opinion in any way. The scene was all for the great leader, who exhorted Ispolkom to declare the Supreme Soviet lapsed. The delegates promptly agreed to the proposal and declared the Executive Committee the only legitimate authority in Chechnya. Once again, the reactions from Moscow were tepid, and mostly superficial. Khasbulatov himself, underestimating the gravity of the situation, he thought that Zavgaev’s replacement would be enough to split the nationalist front in two. Now, according to him, it would be sufficient to force Zavgaev to leave and replace him with Hadjiev, or someone else, to put the radicals in the minority. In reality, what was happening in Grozny was something much more serious than the political game that Khasbulatov thought he was playing. Dudaev had almost all public opinion on his side, he had his armed guards and was setting up a real government.

This was absolutely clear to the First Secretary, and it was even more so when on September 3, ignoring the directives of Moscow, he attempted to introduce a state of emergency through a resolution of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet: no police or army department answered the call. While many of the Interior Ministry Militia men had already changed sides, those who had not taken a position simply avoided moving. Defeated again, Zavgaev remained holed up in the House of Political Education, where he had barricaded himself with his followers. Finally, on the evening of September 6, the National Guard also broke in there: a handful of men led by the Vice-President of Ispolkom Yusup Soslambekov entered the building. It is not known whether it was a premeditated action or the rise of agitation, the fact is that the crowd followed the militiamen and began to devastate everything. The deputies were beaten and silenced. Soslambekov placed in front of each of them a sheet and a pen and ordered them to write their resignations in their own hand. One by one, all the deputies signed. Under the threat of being executed on the spot, Zavgaev signed a waiver in which he “voluntarily” abandoned all public offices. Only the President of the Grozny City Council, Vitaly Kutsenko, refused to sign. When questioned by Soslambekov, he replied: I will not sign. What you are doing is illegal, it is a coup! Moments later Kutsenko flew from the third floor, crashing to the ground. He would later be hospitalized, where he would die in excruciating suffering[2]. The moderates condemned the assault, disassociated themselves publicly and withdrew from the National Movement, constituting an alternative Round Table to Congress. Zavgaev was driven out of Grozny and took refuge in Upper Terek District, his native land. In Grozny, Ispolkom began to operate as a real government, setting up commissions, issuing decrees and occupying public buildings.

In Moscow the news of the insurrection was received almost with disinterest. It took four days before a government delegation, made up of the Secretary of State, Barbulis, and the Minister of Press and Information, Poltoranin, arrived in Chechnya to try to resolve the crisis. With Dudaev, the two tried a “Soviet” approach: in the roaring years of the USSR, when a person represented a danger to the Party and could not be sent to a gulag to clear his mind, he was promoted and kept good. Poltoranin and Barbulis thought that if they offered Dudaev a leading role, he might take the chance to get out of that mess in exchange for a good job and a hefty pension. Unfortunately for them the General wasn’t just smarter than they thought, but he was also more courageous and determined, and he really believed in an independent Chechnya. So the meeting ended in a stalemate.

Khasbulatov meanwhile had returned to Chechnya, where he hoped to resume negotiations with Dudaev where he had left them. The meeting between the two was resolved with a new draft agreement: the “fallen” Supreme Soviet would be dissolved, and in its place a “provisional” Soviet would be established to deal with ordinary administration pending new elections. Representatives of Congress would also have participated in this executive. Comforted by the apparent concession of the nationalist leader, the President of the Russian Supreme Soviet spoke to the masses thronged in Lenin Square. In front of a large crowd (who even spoke of a hundred thousand demonstrators) invited everyone to calm down, asked for the demonstrations to be stopped and put all the blame on Zavgaev, ordering him in absentia not to show up unless he wanted to be taken to Moscow in an iron cage. Finally, when an extraordinary assembly of the Supreme Soviet was convened, he induced the deputies to resign and to establish a Provisional Soviet of 32 members, some from the old assembly and some from the ranks of the Executive Committee. The last act of the Chechen-Ingush Supreme Soviet was a decree calling for new elections for the following 17 November.

Once again it seemed that the situation had been recovered at the last minute, and Khasbulatov set about returning to his duties in Moscow not before Dudaev had fully recommended that the agreements be respected. He did not even have time to land in the Russian capital, which was greeted by a resolution of the Executive Committee of the Congress, just made to vote by Dudaev, in which Ispolkom recognized the Provisional Soviet as an expression of the will of the Congress, and warned him to go against the will expressed by it[3]. The declaration also contained an electoral calendar different from the one agreed: fearful that normalization would weaken their position, the nationalists decreed that elections would take place on October 19 and 27, respectively for the institutions of the President of the Republic and Parliament. Nobody in Moscow knew for sure which president and which parliament they were talking about: the Constitution of the Chechen-Ingush RSSA did not provide for any of these institutions. From the tone of the declaration it was now clear that the National Congress intended to proclaim full independence.

[1]The riots that broke out following the August Putsch had led to the paralysis of government departments, which was beginning to show its first harmful effects on everyday life. On August 28, about 400 inmates from the Naursk penal colony rose up, attacking the garrison of garrison, setting fire to the watchtowers, devastating the service rooms and occupying the prison facility. Two days later fifty of them, armed with handcrafted knives and weapons, occupied a wing of the building. All the others had escaped, dispersing among the demonstrators.

[2]It is unclear whether Kutsenko threw himself from the palace in a panic attack or was deliberately ousted. According to some, it was he who threw himself downstairs, beating his head against a cast iron manhole. Other versions speak of a guard of Dudaev, or of Soslambekov himself, who would have thrown him against a window when he refused to sign his resignation. Even regarding his hospitalization, the testimonies are conflicting. According to some, the angry mob attacked him, filling him with kicks and spit. Others, like Yandarbiev himself in his memoirs, say that Kutsenko was promptly picked up and taken to hospital, but he refused to be examined by any Chechen doctor for fear of being finished. As there were no Russian doctors available, he ended up in a coma, only to expire a few days later. However, the investigation into Kutsenko’s death would not have established any responsibility. The official version reported by the Prosecutor’s Office was that the President of the Grozny City Council voluntarily threw himself downstairs, frightened by the crowd.

[3]The text of the declaration, organized in sixteen programmatic points, began by condemning the Supreme Soviet, guilty of having lost the right to exercise legislative power, of having committed a betrayal of the interests of the people and of having wanted to favor the coup d’état. Some of the main political exponents of the Congress were appointed to the Provisional Soviet (Hussein Akhmadov as President, as well as other nationalists chosen from the ranks of the VDP). The Soviet would have operated in compliance with the mandate entrusted to it by Congress: if a crisis of confidence had occurred, this would have been rejected by the Executive Committee and promptly dissolved. The solidarity of parliaments around the world and of the countries that have just left the USSR was also invoked, in opposition to the attempt by the imperial forces to continue the genocide against the Chechen people.