Do you know what basic conditions were constantly and ambiguously put forward by the West in almost all negotiations with state leaders of the USSR in 1989 – 1991, when it came to providing credit and charitable assistance, and this was not publicized in the Union press? Yes, the creation of that very financial oligarchy (5-10% of the population), capable of controlling up to 60% of the country’s total potential, with the guaranteed establishment of the institution of private property and protection of large-scale foreign investments and foreign property!

Then, strangely enough, the first to realize it and tried to take it into account, albeit limitedly. N.Nazarbayev, but M.Gorbachev for a long time was floundering and hesitated, grasping for various alternatives that were saving in his opinion, but miraculous, as it turned out later, until the whole feud with GKChP broke out, mainly because of irreconcilable differences of opinion among his entourage….

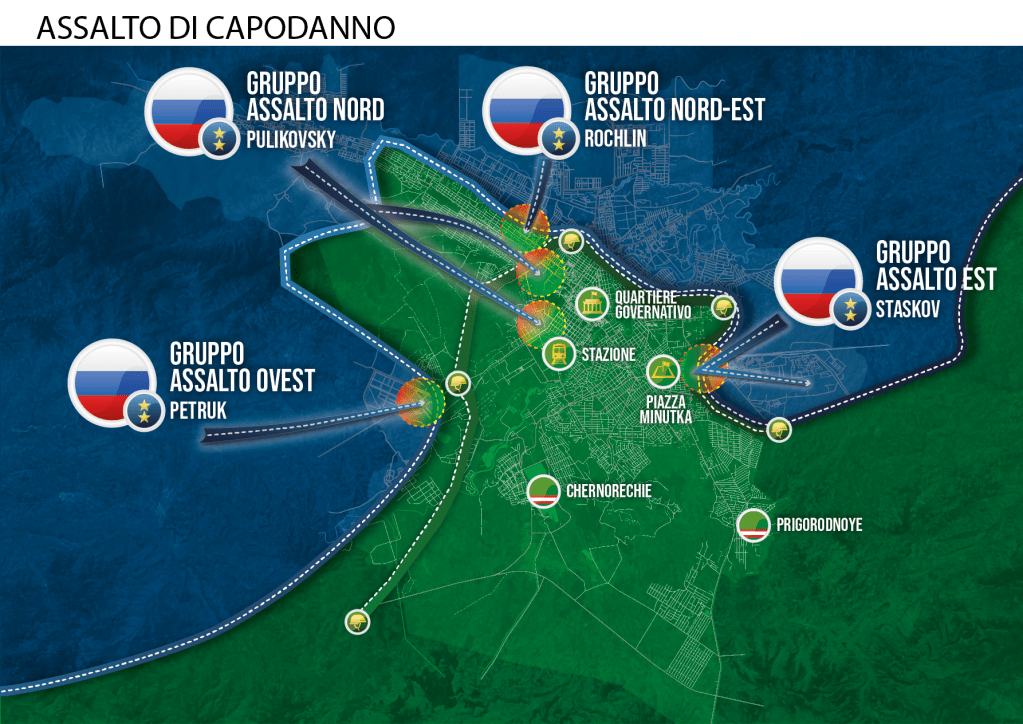

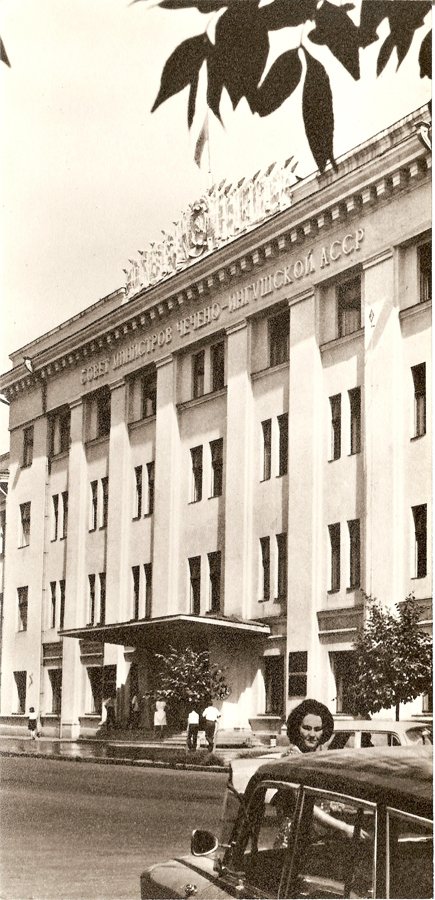

As long as the society reforming towards collegial privatcapitalism does not decisively overcome the transition stage of non-authoritarian state capitalism, which is dangerous because of its instability and centrifugal forces, chaos, crime, economic collapse and general ungovernability in public spheres may reach its peak, followed by monstrous armed conflicts and historically irreversible processes. The example of the collapse of the USSR, the “critical boiling points” in Russia and the CIS countries, and, thank God, only sensitive echoes in the Chechen Republic serve as impressive proof of this.

Back then, in 1984, nothing seemed to foreshadow that such a powerful empire could collapse in such a short period of time by historical standards. And only the highest echelons of power were aware of the fact that the cumbersome and non-adaptive to the ever-increasing demands of the country’s economy management system was failing more and more catastrophically every year, its “slippages” were throwing the USSR further and further away from the advanced countries of the capitalist world in terms of economic development. The “cosmetic repairs” of the state apparatus did not save it, nor did the desperate reshuffling of personnel in it produce any results. That is why, finally, M. Gorbachev, relying on the brave and radical wing of his entourage, decided to reform the state structure. The general public is well aware of the deplorable results of the experiment for the President of the USSR. But what was M. Gorbachev’s mistake, why did he fail to skip the dangerous stage of non-authoritarian state capitalism, even introducing elements of private property and legalizing entrepreneurial activity? Were the centrifugal forces so strong, and the aspirants to the future “financial aces” were still just playing “nursery cooperatives”? Yes, probably. But this was not the only factor.

If one imagines authoritarian state capitalism in the form of the famous Ostankino TV tower, the stability of which is created by the extremely tight steel rope running through it, then the “cable of political stability” of the former USSR consisted of many strands of “unfreedoms” that created the necessary strength. In his attempt to throw the rope bridge from the “top of the Soviet system” to the “Western model”, M. Gorbachev weakened to a greater or lesser extent many of the steel strings, such as freedom of speech, press, information, expression of will, national self-expression…. and even entrepreneurial activity, while leaving the “inviolable” but coveted private property 100% tightened. And while the West was feverishly winding some ropes on its “bay of democracy”, the construction of the Soviet tower staggered and collapsed. The ropes that had already been thrown over did not help; they sagged and plunged us all into the swamp of collegial state capitalism.

The main and also fatal mistake of M. Gorbachev (if only this ERROR!?), was in the FOLLOWING loosening of the strings stretched on the “soviet fingerboard”. The example of “communist China” is clear evidence of this. They do the opposite there and apparently play the “guitar of economic reforms” quite well.

WHAT is the fate of the Russian Federation now? Will “Yeltsin’s sappers” be able to overcome the unfortunate”minefield”for the Union, or is the explosion imminent? Or maybe “Khasbulatov’s” frightened parliament will be able to pull everything back to more familiar circles? What if it all comes back to bite us in Chechnya? Nowadays, few people probably remember the December 1991 speech of Boris Yeltsin. His program speech, made on the 28th after the famous Belovezhskoe deed, although it was verified in parliamentary language and slightly diplomatically veiled for potential Russian tycoons, shone a long-awaited green light as a signal for the most active actions, as an indulgence for the ideals of private property. Behind it stood the little-known fact that the current processes in the Russian Empire (USSR, CIS and the Russian Federation proper) were financed. And it was done by target purpose “under Yeltsin”, who unlike M. Gorbachev, who was bluffing. He gave his consent to the West for the birth of the Russian Financial Oligarchy! International capital already then paid for the first stage, when a person who cannot swim is thrown into the water, seducing him with the pleasure of market relations, which can be obtained on an equal footing with others who have previously mastered swimming in the sea of capital. If he doesn’t drown at once and continues to swim, we will help him a little more, but if he goes to the bottom, we will always find another candidate. It makes no difference who will continue the line of M.Gorbachev and B.G.Yeltsin, be it L.Rutskoy or R.Khasbulatov, but they will not give up what they have, c’est la vie, but that is the logic of the powerful.

Another, and by no means unimportant factor is the fact that Russia has significant healthy forces, high intellectual potential, desire and means to complete the radical reforms that have been initiated. That is, a complete set – Stimulus, Motive, Means and Power.

That is why, summarizing, we can say with great confidence that the young Moscow guild of capitalists, which is emerging and growing stronger day by day, coupled with a foreign armada of “associates”, together with Boris Yeltsin’s team, although rather shabby in battles, but resilient, will bring the matter to its logical conclusion. What is in store for us? Will the mutant virus of the management tools of authoritarian state capitalism (last time in our country it had a variation under the name of “Soviet partam pa ratnoy”), which is stubbornly fighting for living space in the Parliament of the Chechen Republic, as well as in the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Federation, still give rise to incurable metastasis. After all, such a cancerous contagion inevitably dooms the representative bodies of the authorities to become a kind of “reanimated Chechen regional party committee”, taking over from its deceased predecessor the rudimentary functions of control, management and distribution in the sphere of production and consumption, and usurping the right of “the only connoisseur of the interests and problems of the people”.

So what should be our priorities? How, what forces and means should we use in the first place? These are not easy questions, but there are visible answers to them.

Let us first of all realize once and for all one simple axiom. Not a single Parliament of the world and not a single President, sitting in their palaces or residences and issuing only laws and decrees, have not fed a single nation or created commodity abundance for anyone in the history of the world. The welfare of their people is brought, usually by special initiative people (large organizers and entrepreneurs, businessmen and business scientists) who, thanks to their efforts, abilities and talent, often at their own expense and at their own risk and risk, create in society special mechanisms of social and state development, known to them alone and, at first, only understood by them, using as a creative driving force the factor of satisfying the interests of the largest and most productive part of the population. Exactly they, using the personal factor of Means, through the Motive of the attracted specialists, maximally include the factor of Interest of the Producer People, strengthening the factor of Power of the State, which in turn contributes to the next similar cycle, but already at a higher level. As a result, new jobs and guaranteed wages appear in the country, the share of “buy-and-sell” business begins to give way to creative and service business, etc. In short, it is what is called “economic recovery”, the main thing is to legally allow them to do it! And if we can’t do anything to help, it is important not to hinder it, shielding this saving layer of society from aggressive attacks of the “socialist virus” of equality without the rich and hatred of “bloodsuckers”.

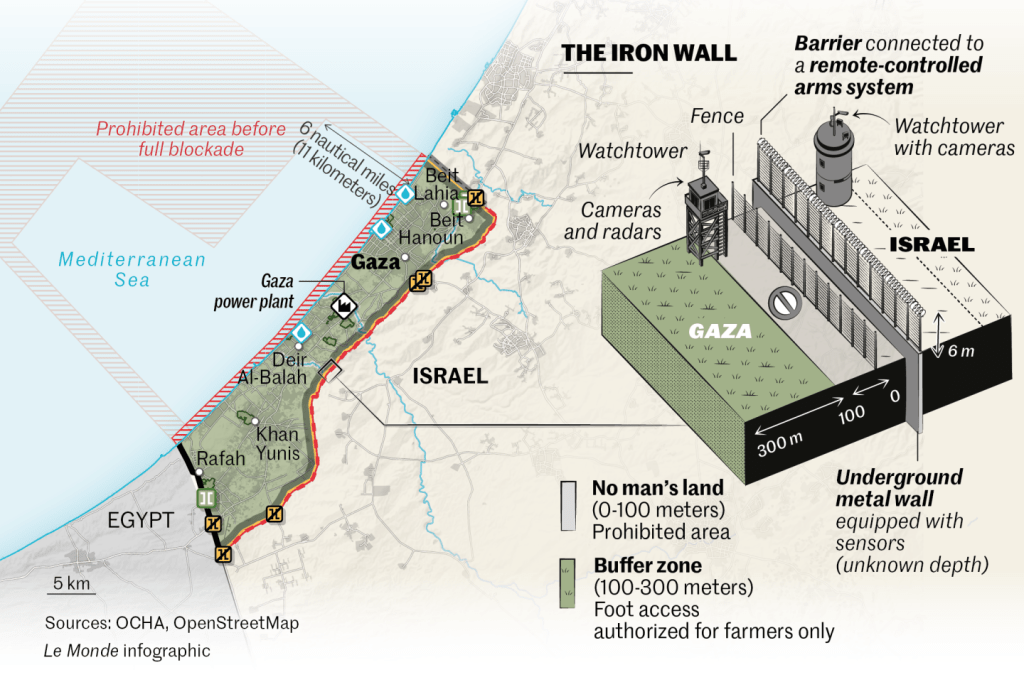

That is why there is no more important task for us today than to create the most possible conditions for the intensive development of the business class, from which domestic Vainakh tycoons of financial and industrial capital will inevitably emerge, the future flagships of the Chechen ship, the guarantors of stability and prosperity of society. It is all the more urgent because, unfortunately, unlike Russia, no one will finance us. Believe me, to the great joy of the Metropolis and not without its handiwork, there are no countries in the world that at this stage would fill the empty niche of the Chechen financial oligarchy as an external friend. The vectors of geostrategic interests of Russia and those states that could actually do it are very different in their directions. The dominant Russian factor of Power and its known unpredictability leaves no one in doubt here. There is no alternative “adrenaline” for us today, and unfortunately there is no minimum necessary start-up capital. At one time we missed a very important moment when COUNCH could have made timid steps and prerequisites for the creation of oligarchic structures, but in the Parliament of the Chechen Republic we defeated the syndrome of the mental deficit acquired from the Bolsheviks. There were other missed opportunities. However, there is a deep conviction, based again on the laws and examples of social development, that the Vainakh people, having unlimited potential reserves, will be able to dispose of them rationally, that a part of the excessive willpower of the present Chechen population will necessarily transform into the missing factors and compensate for any emerging inhibitory moments on its way. And there is no other Alternative to this!

Finally, the last hot topic of discussion of the day is the legitimacy of the current form and content of the state structure of the Chechen Republic. This is a kind of self-branded tablecloth for our political cooks who are losers. Grief-experts of both the domestic and Moscow variety go to what extremes and grave extremes, looking for a speck in someone else’s eye. In order to prevent the “worm of doubt” about the legality of Chechnya from tormenting some people and to finally knock the labeled “trump card” out of the hands of others, the following clarifications are required. If we take a dialectical approach, then legal professionals know that a reference to any law of any country can always be challenged, whether on historical, legal, moral and ethical, or other aspects, due to the fact that jurisprudence is essentially eclectic, i.e. “no wisdom is simple enough”, since one can always find a counterargument to any argument if desired.

It is impossible to create any small-minded code of laws without explicit or implicit contradictions. Humanity has not yet developed a universally-identified, logically adequate and legally sterile language, like computer linguistics, free from such shortcomings. And then on the scales of the disputing parties, in principle, there will always be strong enough competent justifications in their favor, but the adoption of judicial, arbitration, socio-political or any other “legal” decision depends predominantly on the balance of forces and opinions in society, on the power and force positions of the disputing and verdict parties, finally, on the prevailing realities. This has always been the case everywhere, at any level, from the “village council” to the UN General Assembly,

There is no doubt that Russia has not been able to “crush” us after the 1991 secession, but it is also indisputable that Chechnya has not yet won back its position in this dispute. Today we are like two tired wrestlers on the mat who, having entered the clinch, have taken a wait-and-see stance for the final victory throw. A difficult precarious balance for the country. But, remember that Unrecognized Permanent Reality tends to be legitimized sooner or later. It is only a question of time and stamina, and the effort to make it happen. Apparently, just as scientists pharmacists take a long time to reach the required prescription for a new and unexpected disease, our way of choosing the establishment and implementation of rationally effective public administration is also long. It is just that a sick person always wants to get well as soon as possible.

Personally, I see us in collegial privatcapitalism, which, of course, has nationally distinctive features, and I am convinced that the Chechen state has not only a history, but also a real, “not banana” big future, all we need to do is to set the “good Gene Capital” free. If we don’t do it, others will do it.

In closing, I would like to remind you of one thing. Do not forget. The TRUTH is like an infinite mosaic panel consisting of innumerable pieces of “truths”. Truth is one, cognizance of all the immense depth of which, apparently, is not given to a mere mortal, to know it in its entirety is destined only to the Almighty Himself. We are destined to perceive only its separate fragments. Each individual has his own set of “truths”, from which he can make his own part of the canvas of truth. How much of it will he really display, of what components is it composed of, and what should they be? These and other similar questions, have not yet been identified in our society.But I believe in the collective Vainakh capabilities, in the Chechen Stimulus and Motive, capable of painting the necessary picture of the Truth, however small in size and large in number its components may be, because behind each of them stands our

Man with his priceless destiny

PEACE, TRANQUILITY AND PROSPERITY TO YOU ALL.