On 16 April, a few hundred meters from the village Yarish-Mardy in the Argun Gorge, the Russians suffered one of their worst setbacks. At 2:20 p.m., after a several hours’ march from Khankala Military Base, an armored column of thirty fighting vehicles,[1] four oil trucks, and numerous supply trucks, hit a bottleneck between the villages Chishki and Zony. The area was the only along the route without a permanently-manned Russian checkpoint and, due to the differences in height between the road and hills, without radio coverage too. Waiting there instead were Chechen units led by an obscure young commander of Arab origin. He had arrived in Chechnya in mid-1995 leading a small group of foreign fighters. Now with 80-160 men, his name was Samir Saleh Abdullah but went by Ibn Al Khattab.[2]

The ambushers jammed the radios of the passing unsuspecting Russians before detonating a powerful anti-tank mine, stranding the forward vehicle. The hills began spewing down on the column, now stretched for almost a kilometer and a half, destroying the leading and trailing vehicles, and a few minutes later killing the commander and deputy commander, Major Terzovets and Captain Vyatkin. Most of the infantry and vehicles were destroyed eventually too. A nearby platoon of Russian soldiers set off to investigate the explosions. Hearing the nearby explosions, a platoon of Russian soldiers set off to investigate but came under heavy fire too and took up defensive positions. The command hurriedly organized a task force with battle tanks and heavy machine guns to relieve their trapped comrades. Simultaneously, a second relief column supported by combat helicopters was racing to the south. The two rescue teams made contact with the Chechens around five o’clock and fled to the woods an hour later. They had arrived at the ambush site to the smell of a hundred of their dead comrades burning. Of the initial 30 vehicles 21 were destroyed, and of the 200 men only 13 were unharmed. The Chechens lost twenty at most.[3] This was a defeat which blew up the tottering diplomatic bridge unilaterally constructed by Yeltsin. The day after the ambush, the Russian president backtracked, vowing not to “deal with the gangsters.” Meanwhile, Yarish-Mardy projected a hitherto unknown name, Al Khattab, onto the fresco of freedom fighters. With the advent of the internet, he had prudently brought a troupe of cameramen to record for a propaganda film, resulting in global clicks and new sympathizers for the Chechens. For the first time, footage out of Chechnya showed not helpless victims of Russian bombardment or desperate fighters, but a formidable fighting force winning true battles against Russia. The video of the Yarish-Mardy ambush evidently reached Parliament in Moscow: deputies requested an immediate report from Grachev and ordered the creation of a parliamentary commission of inquiry. As a result, formal accusations were brought against commanders of the devastated unit, but also the unified command of forces in Chechnya, for authorizing the column’s mission without properly assessing risks, even Grachev could not escape an accusation. Tough lessons went unheeded though, with another ambush on a Russian column destroying 15 combat vehicles and an unknown number of men on 5 May.

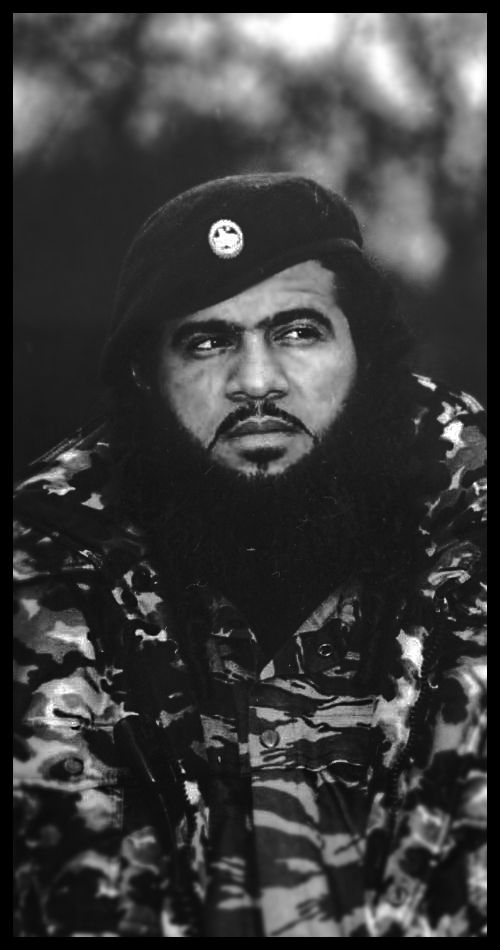

Khattab, whose fame would continue to grow with such attacks, needs to be put into context. He was a follower of Salafism, a radical current of Islam of which some fringes, called Wahhabism, openly preached global Jihad while supporting terrorist organizations such as Al Qaeda. Born in Arar, Saudi Arabia in 1969, he grew up passionate about Islam’s great figures, developing a radical vision of religious commitment that had led him to join, at seventeen years old, the Afghan Mujahedeen’s war against the Soviet Union. Earning the nom de guerre inspired by Caliph Omar Ibn Al- Khattab, he bore a permanent mark of that war after carelessly handling explosives and almost losing his entire right hand. According to his memoirs, between 1993 and 1995 he served in Tajikistan alongside the Islamic opposition and then moved to Bosnia.[4] More than just a strong fighter, he was an astute strategist and diplomat, skillfully commanding media to build a network of financiers. Cameramen captured the successes of his Jihad to show to the fringes of the Islamic world. Khattab was the first and certainly the main non-native commander to attract news in Chechnya.[5] After entering under the guise of a Jordanian journalist with his crew, he connected with Faith Al-Sistani, the commander of an Islamic battalion who led him to Dudaev.[6] With the president’s approval he settled down with some of his followers in an old Soviet Young Pioneer camp near Serzhen-Yurt.[7] Here Khattab set up a training course using his experience on previous battlefields: guerrilla warfare, explosives, and ambushes, focusing on how to transform a band of militiamen into a deadly combat force.[8] Though, what set his and other Chechen units apart was a strict adherence to the dictates of Islam. The war planted the seeds of Islamic formations by increasingly radicalizing the rural population.[9] According to Khattab, his “Jamaat’s (literally “community”, as was customary to call Islamist guerrilla military cells) first action was an ambush near Kharachoy, feeding a Russian column through the meat grinder. The initial success attracted new blood for the Yarish-Mardy ambush already described. Inflicting this second debacle on the Russians, Khattab won respect as a field commander and a seat on the Defense Council, the executive body through which Dudaev directed his armed forces. His invitation to the Defense Council marked the beginning of the so-called “Islamization of the resistance.” Until then, nationalism had been the common denominator across Chechen military groups.

Two overwhelming factors encouraged the gradual Islamization of the Chechen resistance: the population’s suffering and the successes of field commanders associated with Islamic radicalism. In 1996, the sectarian view of the war for independence was in its infancy but growing fast. It is unsurprising that, with most of the population displaced, ravaged by poverty, and grieving over lost loved ones, people turned to extremism. Yandarbiev’s and Ugudov’s rhetoric fed the public with a holy war of independence against “Russian infidels.” The rule of law having died, Islam was a a simple and easily understandable replacement for a nation unaccustomed to the law of war. Next, political isolation incentivized supporting Jihad as desperate tool for gaining financial support from numerous religious networks across the Arab world. In exchange, these backers demanded the Chechens fight not for simply national aspirations but divine above all.

[1]According to The War in Chechnya, the column carried 199 men, mostly contract soldiers.

[2]According to what Khattab himself later reported, his contingent did not exceed 50 people. The Polish journalist Miroslav Kuleba, who entered the independence guerrilla, declared in his book The Empire on its knees the figure of 43 men, including Khattab.

[3]As reported by Ibn Al Khattab in his book of memoirs, the Shahid (“martyrs”) were 9, and 21 were wounded. On the Russian side, Chechen losses were never ascertained with certainty. The only certain data were the bodies of 7 militants from the Shatoy District, identified on the battle site in the following days.

[4]Most of Khattab’s autobiographical notes are contained in a book of memoirs, Memories of Amir Khattab , some extracts of which can be found on www.ichkeria.net in the Insights- Memoirs section.

[5]About his choice to participate in the war in Chechnya, Khattab says: “While we were preparing for the next year, the events in Chechnya began. I watched TV: the fight against the Russians was led by the communist general Dzhokhar Dudayev, or so we imagined. We thought it was a conflict between communists, we didn’t see Islamic prospects in Chechnya. One day I went back to the rear to nurse my wounded right arm. There a Chechen Mujahideen came to me and offered to take me to Chechnya for a week or two. We looked at the map of Chechnya. It was a small republic of 16,000 square kilometers. It was even hard to find on the map. I thought its population was a thousand […].”

[6]Regarding this meeting, Khattab recalls: I met Dudayev during a visit to Sheikh Fathi. […] Dzhokhar began to ask questions. […] He asked: “Why don’t they come to help us in your area?” I replied, “The truth is that the reasons for the war are not clear, and people don’t know what we are fighting for.” He told me: “Brother […] this is an Islamic land. Isn’t that enough for you?” […] I sat down next to them (Dudayev and Al – Sistani, ed.) and asked Dudayev the first question: “What is the purpose of your battle? Do you fight for Islam?” He replied: “Every son of Chechnya and the Caucasus, oppressed for decades, dreams that one day Islam will return not only to his homeland, but to the whole Caucasus. And I am one of these children.[…].”

[7]We have already mentioned this field in the paragraph concerning the Battle of Serzhen- Yurt.

[8]Regarding the establishment of the Serzhen Yurt camp, Khattab recalls: […] I remember that at the first meeting there were more than 80 mujahideen who have now become Emirs. I remember what I told them (and Fathi translated): “If any of you want to be Emir, then he must offer his fighting program and we will obey him.” Nobody said anything. In those days the battle was approaching the mountains. So I told them, “I’m not telling you that I have knowledge. I only have combat experience in Afghanistan and Tajikistan. Maybe it’s time to get to work. I have a program staggered into three phases: preparation, arming and operations. If we are not ahead of you in battle you can shoot us. We will be in front of you after the course. After arming, we will start implementing the combat program. We will always go ahead of you, I and the brothers who are with me.”

[9]Again we quote Khattab’s recollections, contained in his memoir: The fighting soon approached our area. The young people argued whether it was a Jihad, the Sufi mullahs declared that it was not, that it was a showdown between Dzhokhar Dudayev and the Communists, and the hypocrites added fuel to the fire […]. The puppets of the Russians (the anti-Dudayevite opposition, ed.) said that this was a problem between them and Dudayev, and that we shouldn’t have intervened. […] I didn’t really know the situation because I hadn’t studied it. I had a video camera and started filming people, asking them what they were fighting for. That’s how I met Shamil Basayev. Some people thought I was a reporter. I have seen sincere people and, I swear by Allah, I cried when I asked an old woman, “How long will you bear these hardships?” and she replied: “We want to get rid of the Russians.” I asked her “What are you fighting for?” and she replied: “We want to live as Muslims and we don’t want to live with Russians.” So I asked her. “What can you give to the Mujahideen?” And she: “I have only this jacket on.” I cried: if this old woman can help by having only this, why do we allow ourselves to be afraid and doubtful? From that day I decided with my brothers to start preparing people for battle, as a first step.