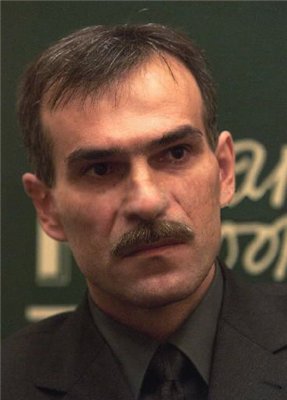

The following is the transcript of the first part of the interview between Francesco Benedetti and Akhmed Zakayev conducted by Inna Kurochkina for INEWS (we attach the link to the original video, which will soon be accompanied by English and Italian subtitles)

On 6 March 1996 the armed forces of the ChRI launched their first major offensive action of the conflict: the so-called “Operation Retribution”. According to what I was told by Huseyn Iskhanov, then Representative of the General Staff, the plan was conceived in Goiskoye and saw your participation, as well as that of the Chief of Staff, Maskhadov, and the Deputy Chief of Staff, Saydaev. Do you remember how you planned this operation?

Yes, of course I remember that. This, in principle, came out of the operation that we carried out to blockade the city of Urus-Martan in order to prevent elections. After this operation, my Chief of Staff Dolkhan Khadzhaev and I met with Dzhokhar Dudayev. And we suggested the option that something like this should be done. We understood that any of our actions in order to make any attempts to change this situation, the Russians needed at least three days, theoretically.

It took them three days to recover and start doing something. And then we started talking about the possibility of blocking several districts at the same time. And then Dzhokhar Dudayev said: “You see how good it is when a team works. I, he says, was with these thoughts and thought about how best and what kind of operation we should carry out.

It was then that the idea arose to carry out this operation in the city of Grozny, in the city of Dzhokhar – in the future.

And on the same day, it was decided to invite Aslan Maskhadov, Chief of the General Staff, to call him to our side, and from that time, almost two or three days after we discussed this with Dzhokhar Dudayev, we began preparations over this operation. Practically – we had our own intelligence in Grozny, we knew where each Russian unit was concentrated, and we did additional work and identified all these points where Russian units are located. Where are checkpoints, commandant’s offices, military units.

Yes, Umadi Saidaev, the late Umadi Saidaev, he was the Chief of the Operational Headquarters, and then, later, Aslan Maskhadov arrived there, and together with the Commanders of the Directions who were supposed to take part, we developed this operation.

Returning again to Operation Retribution, this was a success that the ChRI leadership chose to use more symbolically than strategically. In your memoir you recall that at the time the decision to withdraw from Grozny, despite having taken it under your control, did not please you, and that even now you maintain that what was achieved in the following August, with Operation Jihad , could have been achieved with Operation Retribution. Finally, you say: In March of 1996 we probably had the opportunity to finish the war victoriously, and then much of our recent history could have gone differently. What do you mean by this sentence? Are you alluding to the fact that Dudayev was still alive, or to the fact that the Russian presidential election had not yet been held? Or again, to something else?

I thought about the elections in Russia last, because there have never been any elections there. Yes, the very fact that Dzhokhar was alive at that time could have been of great importance, and the course of history could have been completely different if the war had ended with Dzhokhar Dudayev alive. And it is unlikely that the Russians would go for it, I also admit this, on the one hand, I admit that they would not go. They made every effort to eliminate Dzhokhar Dudayev, and subsequently to seek peace. As for this operation, I’m just sure of it. Yes, then we planned the operation for three or four days, but there was no concrete decision, such that we would leave in three days. Because Dzhokhar Dudayev arrived in Grozny, he was at my Headquarters in the city of Grozny, in my defense sector, in that part of the operation that the units under my command took part, he arrived there, and we were together last night at our headquarters. And I remember the reaction of Dzhokhar Dudayev when he learned that there was an order to leave the city, that some units had already begun to leave Grozny. He did not agree with this, because you can really assess the situation when you see the situation in the process, how it changes, and based on this you must draw conclusions and make decisions. Dzhokhar Dudayev was in Grozny for the first time after the Russian occupation, we traveled with him at night, in Grozny at night, we went to the bus station, he watched all this destruction, and when we returned to the Headquarters, some of our units had already begun to leave. He said: “Well, if there is an order, it is necessary to carry it out.”

And we retreated. And I later thought about it, because nothing more than what we did for the month of March, we did nothing in August. This operation was repeated one by one in the same way, and with the same forces and means. Even in August, we initially had and at the beginning of this operation, the funds involved were two times less than in the March operation. And therefore, I am sure that if we had stayed in Grozny … (well … history does not tolerate the subjunctive mood). What had to happen happened. But I remain of my opinion that it could have been different. But this is already from the area of \u200b\u200b”could”.

But that did not happen.

In March 1996 you faced, as commander, what was perhaps the biggest defensive battle fought by the Chechen army in 1996. I am referring to the Battle of Goiskoye. I’ve read conflicting opinions regarding the choice to face the Russians in that position. Some argue that the defense of the village was senseless, resulting in numerous unwarranted casualties for the Chechen forces. Others argue that if Goiskoye had fallen too soon into federal hands, the entire Chechen defense system could have shattered. After all these years, what do you think?

To prevent the enemy from reaching the foothills, to block him in the village of Goyskoe, this was, from a strategic point of view, militarily an absolutely correct decision. This decision was made by the Supreme Command of the Armed Forces of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria. Yes, I also know that there is such a statement, but based on real losses, we did not suffer any serious losses during the defense of Goisky. Yes, there were dead, several people who died were injured, but there were no such losses. There is no war without loss. Well, in a strategic sense, the protection and defense of Goisky kept the front line, which moved from Bamut to Alkhazurov. Alkhazurov fell under Russian control, but Komsomolskoye also fell under Russian control. But in Goyskoe we didn’t let them go any further. We prevented the passage of the Russians up to the foothills. And thus they retained the Front and the front line. And this was of very important strategic importance, all the more so against the background of the fact that the Russians began to talk about negotiations, about a truce. If we talk about a truce and start a conversation with them about a political dialogue, naturally, the preservation of a certain territory that we controlled, this was of great political importance, and in connection with this, Dzhokhar Dudayev made the decision to protect Goiskoye. Yes, we lasted a month and a half. And later, after the death of Dzhokhar Dudayev, when Bamut had already fallen, it was decided to leave Goiskoye. But as long as Achkhoy and Bamut were on the defensive, we held the line of defense in Goyskoye as well.

But when the front had already been interrupted there, it was pointless to continue to hold the front line and lose our fighters. And so it was decided to withdraw our units already to the mountains. Subsequently, we already redeployed closer to the city and began to prepare for the August operation.

After Dudayev’s death, power was transferred to Vice-President Yandarbiev, who took office as Interim President. Was the decision to transfer power to him unanimous? Or were there discussions about it?

In principle, there were no discussions, one vote was against, the rest all spoke in favor of recognizing Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev as Vice President. It was in line with our constitution, presidency provision, and it was accepted. And Zelimkhan Yandarbiev began to act as President.

After Yandarbiev assumed presidential powers, he appointed you as Presidential Assistant at Security. What were your duties in this position?

Yes. He appointed me Assistant to the President for National Security. And at the same time, that unit, that is, the Third Sector, which I commanded, I was simultaneously appointed Commander of the Separate Special Purpose Brigade. That is, the unit that I commanded, being the Commander of the Third Sector, he was also transferred to the Brigade, to the status of the Brigade under the President of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria. Basically, this was done because Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev, after we retreated and put up the Presidential Palace at the beginning of the war, he was inside the Presidential Palace until the last moment, until we left the city. Since that time, in principle, Zelimkhan Yandarbiev has not been involved in military operations, and over the past year and a half, over the past year, new units have already been created and new people have appeared in these military structures. And naturally, Zelimkhan needed a person who knew this whole system militarily, and, of course, we worked with him and in the near future Zelimkhan was introduced to the course in all Directions, Fronts and our units, and already as the Supreme Commander, he Subsequently, he began to manage these processes himself. And my task included power components. And later it was transferred, after graduation this position was transferred, retrained to the position of “Secretary of the Security Council”.

And before the elections, in principle, I performed these functions.