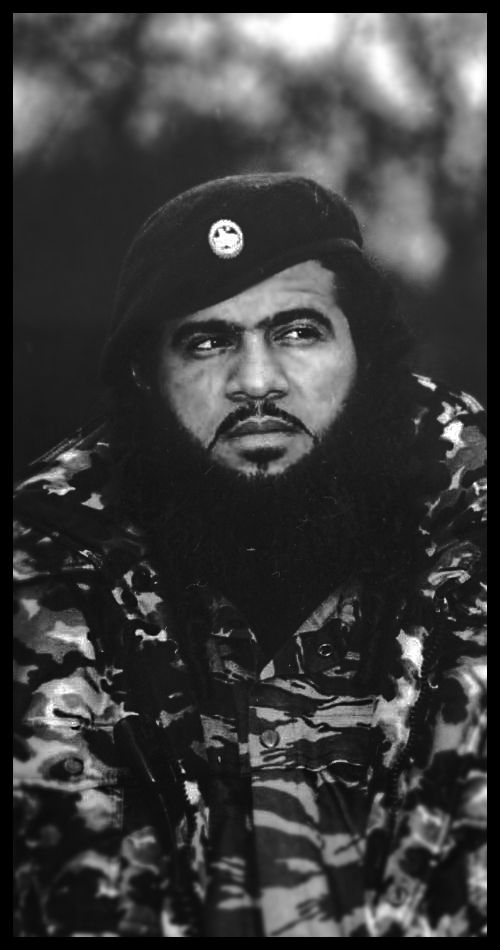

The story of Salman Abuev – a Chechen soldier and official – embodies the contradictions of Chechnya in the 1990s. A distinguished fighter in the First Chechen War, Abuev was honored as a national hero of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, only to be branded a traitor after joining the pro-Russian side. He became a key collaborator of Akhmat Kadyrov during the Second Chechen War, and was killed in an ambush in September 2001. Below is a biographical profile that traces his career, contextualizing it within the Chechen conflict and reporting the assessments of both sides.

Background and Education

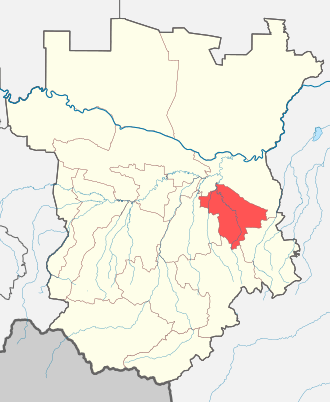

Salman Abuev was likely born in 1962, originally from the village of Alleroy in the Kurchaloy district. We lack detailed information on his early education, but his figure emerged during the First Russo-Chechen War (1994-1996). Abuev immediately joined the pro-independence camp and fought in the Ichkerian Army, reaching the rank of colonel. He distinguished himself for his military merits during the conflict, earning the respect of the state’s leaders: at the end of the war, the new president, Aslan Maskhadov, promoted him to the rank of Brigadier General and awarded him the “Honor of the Nation” decoration, one of the ChRI’s highest decorations. This decoration—conferred personally by Maskhadov—attested to Abuev’s courage and dedication in the struggle for independence.

With the peace that followed the Khasavürt Accords and the election of Maskhadov (1997), Abuev initially became involved in the power structures of the newly independent republic. For a short time, he served as chief of the Kurchaloy district police, his home region. Subsequently, in the spring of 1997, Maskhadov promoted him to a more senior role, appointing him head of the Department for the Protection of State Property, an office primarily responsible for combating oil theft and illegal refining, endemic scourges of the postwar Chechen economy. This position, also known by its Russian acronym DOGO, was particularly prestigious, as it placed Abuev in charge of protecting the entire national oil sector. In this capacity, he also commanded an armed unit tasked with guarding extraction facilities and suppressing illicit trafficking.

Military and Political Career

Despite his prominent role in post-war Ichkeria, Abuev clashed with some of Maskhadov’s leadership. In particular, according to Russian sources, he openly criticized Maskhadov for the growing tolerance of radical Islamist groups (the “Wahhabites”) in Chechnya in the late 1990s. These political frictions strained his relationship with the president. On April 5, 1999, Abuev was dismissed from his post as head of the State Property Department by Maskhadov, because he was deemed “incapable of putting an end to oil theft.” As a result, he was demoted to lower-level positions: Maskhadov transferred him to head a district police department (according to some sources in the Gudermes district, according to others back in Kurchaloy). During this period, operating in the field far from the capital, Abuev encountered the climate of growing instability and became better acquainted with Akhmat Kadyrov, then Mufti of Chechnya. In Gudermes, Kadyrov—despite being part of Maskhadov’s government—was taking increasingly critical stances and paving the way for a possible agreement with Moscow.

In August 1999, the situation escalated: the armed incursions of commanders Shamil Basayev and Emir Khattab into Dagestan drew a clear condemnation from Kadyrov. Kadyrov and Abuev, now allies, issued a political ultimatum to Maskhadov, declaring that they would cease supporting him unless he publicly condemned the actions of the guerrillas who had entered Dagestan. This was the breaking point: at the outbreak of the Second Russo-Chechen War (October 1999), Abuev made his final choice, siding with Akhmat Kadyrov on the Russian side.

In the fall of 1999, Abuev—now Brigadier General—and Sulim Yamadaev (another influential local commander) withdrew their units from Gudermes, allowing Russian troops to take control without a fight. This act amounted to a surrender of Chechen territory’s second largest city and was a key event: in response, President Maskhadov accused Kadyrov, Abuev, and the Yamadaev brothers of treason, while the Ichkeria Sharia Court sentenced them in absentia to death for high treason. Abuev switched sides in the conflict: he publicly repudiated Maskhadov in the very first days of the Russian operation and declared his support for Mufti Kadyrov, who would become the head of the pro-Russian interim administration in June 2000.

Within the nascent collaborationist government, Abuev soon became one of the few former high-ranking separatist commanders to switch sides. Moscow, however, did not place complete trust in these figures: in 2000, Abuev was even arrested by the federal military, perhaps on suspicion of double-dealing. Akhmat Kadyrov had to intervene at the highest levels—apparently with the direct support of the Kremlin—to secure his release. This demonstrates the ambiguity of Abuev’s position in those months: by now unwelcome to the separatists, he was not yet fully integrated into the new pro-Russian system. Kadyrov, however, considered him a highly valued collaborator and personal friend; he took him with him on sensitive political missions, such as a trip to Strasbourg to the Council of Europe, where Abuev and Kadyrov appeared side by side to denounce the Maskhadov government. Abuev also championed a conciliatory stance: he appeared on local TV urging Chechen guerrillas to lay down their arms and return to civilian life, following the Kremlin’s previously dictated strategy of thinning out separatist lines through calls for reconciliation and individual amnesties.

Shift to the pro-Russian front

In the second half of 2000, with Russian control over lowland Chechnya consolidated, Kadyrov began appointing his own trusted personnel to local administrations. Salman Abuev, though disliked by his former comrades, had military experience and knowledge of the territory, as well as personal ties with Kadyrov. Kadyrov lobbied for a prominent role in the new apparatus: after much persuasion, in August 2001 he obtained Moscow’s approval to appoint Abuev as head of the Internal Affairs Department (OVD) for the Kurchaloy district. Paradoxically, Abuev found himself holding almost the same position he had held under Maskhadov (head of the district police), but this time within the pro-Russian administration.

According to local accounts, a dramatic event convinced Abuev to accept this assignment and become actively involved in the field: in August 2001, during a large-scale “zachistka” (anti-partisan roundup) operation conducted by federal forces in his home village of Alleroy, many civilians were subjected to abuse and violence. Shocked by what had happened to his community, Abuev decided to take over the leadership of the district police to protect the local population and restore a modicum of order. As a former commander known and feared in the area, he acted with a certain autonomy towards both Maskhadov’s men and the federal military, attempting to apply the law impartially. During the few weeks he was in charge in Kurchaloy, he took courageous initiatives: for example, he ordered the temporary detention facility (IVS) to be moved from the military komendatura base—where civilians were often mistreated—to a building under the civilian jurisdiction of his OVD, “as required by law.” He also insisted on dismantling a notorious military checkpoint between Kurchaloy and the nearby village of Mayrtup, notorious for extorting passersby. These moves earned him the favor of some residents, tired of the security forces’ excesses, but angered some elements of the federal apparatus, whose presence guaranteed Abuev a modicum of protection.

Shortly before his death, Abuev had a public clash with the local FSB chief: as witnesses in Alleroy reported, the Chechen general rebuked the FSB officer for his brutal methods against civilians and declared that he would not tolerate further abuse, threatening to turn directly to FSB director Nikolai Patrushev in Moscow if necessary. This episode highlights how Abuev was balancing two fronts: on the one hand, he sought to demonstrate loyalty to the Russians by ensuring order; on the other, he maintained a firm stance in defending the population, attracting enmity both among the separatist ranks and among some circles of the federal forces.

Death

On the evening of September 20, 2001, about a month after taking office in Kurchaloy, Salman Abuev was ambushed. While driving home with his younger brother and several fellow police officers, his vehicle was attacked by a group of armed, masked men near the road between Kurchaloy and Mayrtup. The attackers opened fire at close range, riddling the car with bullets and killing Abuev instantly along with six people accompanying him. Among the victims were Salman’s brother, Ayub Abuev (18), and several officers originally from Alleroy (Sultan Temirbulatov, Sultan Usmanov, Yusup Darshaev), as well as two other local police officers. According to some reports, Abuev attempted to retaliate by firing several shots with his service pistol, possibly wounding one of the attackers, but was overwhelmed by the crossfire. A few minutes later, other OVD officers from Kurchaloy arrived, but they too were ambushed.

Abuev’s elimination was a severe blow to Akhmat Kadyrov: Salman was one of the very few former commanders of the ChRI army who had defected to his side. Kadyrov personally visited the village for the funeral, but the ceremony was marked by tensions – Russian soldiers at the Alleroy checkpoint blocked access to the funeral procession for a long time, leaving dozens of people who had come to pay their respects stranded. Abuev’s murder by the rebels was part of a spiral of targeted violence against pro-Moscow administration officials: just six days later, Kurchaloy’s deputy district commander, Sheikh Dugaev, was also assassinated, and in the following weeks, other local officials suffered the same fate. This campaign had a specific purpose: to intimidate and “morally” undermine Akhmat Kadyrov, systematically depriving him of his most valuable collaborators and discouraging any further defectors.

Historical Assessment

On the political and propaganda levels, Salman Abuev was viewed diametrically opposed by the two warring sides. For the Republic of Ichkeria, Abuev was now a renegade: the Maskhadov government formally removed him from all ranks and honors previously awarded to him, including revoking his title of “Honor of the Nation” and posthumously demoting him. As already mentioned, an Islamic court had sentenced him to death in 1999, and his killing was greeted by separatists as the execution of a traitor. On the pro-Russian side, however, Abuev was presented as an example of a Chechen patriot who had abandoned the extremist cause to embrace the path of peace under the Federation.

Akhmat Kadyrov publicly mourned his passing, calling it a grave personal and political loss, and praised Abuev’s courage in fighting the “terrorists” to the point of ultimate sacrifice. Local government sources emphasized that Abuev had died “in the line of duty” while resisting an ambush by a numerically superior terrorist group. In subsequent years, Chechen officials remembered Abuev as a “hero,” and commemorations in his honor were held in Kurchaloy; Ramzan Kadyrov himself (Akhmat’s son) visited his grave.