Following a conversation with journalist Maria Katysheva, we publish her corrections, as a further summary of the article on the Presidential Palace.

“The article on the presidential palace is generally interesting and informative, the symbolic meaning of this object is revealed very accurately; I have comments only on the paragraph concerning the history of the construction : ” THE RESCOM With the return of Chechens and Ingush from the 1944 deportation, the new leaders of Chechen-Ingush launched an ambitious urban plan in the city of Grozny to accommodate the hundreds of thousands of former – exiles who were returning to the country. The centerpiece of this building project was the Communist Party Palace, called in acronym Reskom: a ream of Moldovan architects and engineers was recruited to build it…”

The wording of this text raises questions. It follows that the grandiose development of Grozny, the main element of which was RESCOM , is associated with the return and placement of exiles, that is, it began in 1957. It turns out that Reskom also began construction at the same time. In fact, it went differently. Let’s look at it in order:

With the return of Chechens and Ingush from deportation in 1944 , the new leaders of Chechen-Ingush began to implement an ambitious urban plan in the city of Grozny to accommodate the hundreds of thousands of former exiles who were returning to the 1944 , the new leaders of Chechen-Ingush launched an ambitious urban plan in the city of Grozny to accommodate the hundreds of thousands of former – exiles who were returning to the country).

There are two mixed phases here. One is from the 1950s -’60s. The second is the 1970s -’80s. During these periods the republic was ruled by different peoples and the historical situation developed differently.

1950s-60s. Chechens returned from deportation in 1957. There was no urban development plan specifically designed to “accommodate hundreds of thousands of former exiles.” On the contrary, Chechen-Ingush leaders at that time were opposed to the restoration of the republic and organized mass protests themselves against the return of the exiles. They were Stalinists, they did not like the policies pursued by Khrushchev, later some of them even participated in his overthrow. With their approach to the issue of the restoration of the Chechen-Ingush Republic, they could not accommodate the former exiles and take care of their accommodation, so very few Chechens settled in Grozny. In the late 1950s and early 1970s, these leaders pursued a disastrous national policy and did so many stupid things that they were removed from the leadership of the republic. Of course, in those years construction was under way. But to call the development ambitious, especially to accommodate the exiles, would be an exaggeration.

1970s – 1980s. New leaders ( new leaders) arrived in the republic only in the mid-1970s : the first secretary of the regional party committee A. Vlasov and the first secretary of the Grozny city party committee N. Semenov. Thus they began the grandiose restructuring of Grozny. They looked at the capital of the republic with new eyes and saw that the largest industrial center in the North Caucasus, with developed industry, looked like a large village. At that time, entire neighborhoods consisted of brick houses, even in the center huts from the days of the Grozny fortress were preserved. Then an ambitious plan to rebuild the city appeared. (Great new leaders of Chechen-Ingush launched an ambitious urban plan in the city of Grozny.) But this had nothing to do with the placement of the former exiles: by then they had already settled down.

2. The centerpiece of this building project was the Communist Party Building , called by the acronym Reskom: ( The centerpiece of this building project was the Communist Party Building , called in acronym Reskom ) .

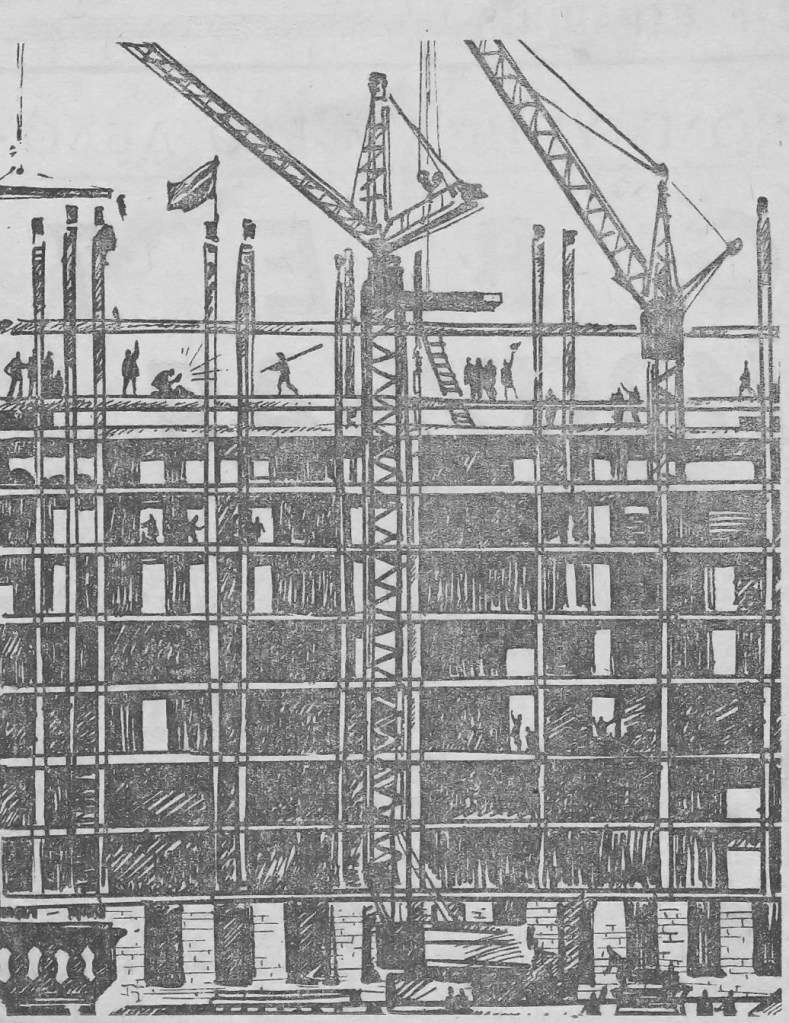

There were several mainstays of Grozny’s reconstruction plan in the late 1970s and early 1980s: Minutka Square, a public garden near the main post office, a theater and adjacent square, the station square, and much more. Grozny then turned into a huge construction site. The main focus was in fact Resk. Previously, the office of the PCUS regional committee was located in a small old building designed in the Oriental style. Once upon a time, in pre-revolutionary times, financial and commercial facilities were located here. Neither its appearance nor its history corresponded in any way to the important position occupied by the Communist Party in the Soviet Union. The material embodiment of its power and significance, the personification of its inviolability should have been a truly grand and imposing building. The new leaders of the republic, A. Vlasov and N. Semenov, set out to build it.

3. …a team of Moldovan architects and engineers was recruited for its construction. ( A ream of Moldovan architects and engineers was recruited to build it).

Yes, you can find the following information on the Internet: ” Reskom was built in the early 1980s according to a standard design by Chisinau architects.”

It appears from this text that it was Moldovan architects and builders who worked on this object from start to finish, as if there were no specialists in the corresponding field in Chechnya. This is wrong.

Vlasov and Semenov, in fact, entrusted the implementation of their idea to the architects of the Chechinggrazhdanproekt design institute, but they were not satisfied with the result of the work. Just at this time, two independent masters with extensive experience in urban planning came up with a counterproject: sculptor-monumentalist Alexander Safronov and architect Yakov Berkovich. The project they proposed was unconditionally approved, as it corresponded in all respects to the clients’ plans. Further work on this project was carried out at the Chechinggrazhdanproekt Institute, and Safronov and Berkovich were included in the staff, the entire detailed development process taking place with their direct participation; It is possible that at some point Moldovan architects and engineers were involved , but this can in no way serve as a basis for claiming that they “built the Reskom in Grozny.” In the design documentation, the authors were Safronov and Berkovich.

It is worth noting this point here. The fact is that in the Soviet Union objects of similar importance were built according to standard designs. Perhaps Moldovan architects were precisely the originators of a standard design, but that does not make them the builders of the Grozny administrative center.

A standard blueprint is a kind of base that architects can rely on while executing a specific order. Relying does not mean copying. The specific characteristics of each region require individual development and not mechanical adherence to the recommendations set in the standard design. If one compares the Grozny Reskom with the PCUS office in Chisinau (it was definitely built by Chisinau architects), one sees that despite some similarities, these are completely different objects. With different character, so to speak. The same ambitious political and propaganda idea in Chisinau and Grozny has different figurative incarnations. Because the authors are different.

When Doku Zavgaev became head of the Chechen-Ingush Republic, he returned the administrative center to the old office with oriental architecture. The Reskom building was transferred to the diagnostic and therapeutic center.

Maria Katysheva’s biography

Thirty years of journalist Maria Katysheva’s life were spent in Chechen-Ingushia, almost twenty of them – as a correspondent for the republican newspapers “Komsomol Tribe” (renamed: “Republic”) and “groznensky worker” (renamed: “Voice of Chechen-Ingushia” – “Voice of the Chechen Republic”). She has authored and organized topical publications on socio-political and historical issues. And the discussion conducted at her initiative and with her participation among Chechen-Ingush and North Ossetian scientists on controversial territorial issues had a particularly wide resonance: a detailed account of this discussion received the value of the paper.

From 1991 to 1993, M. Katysheva was a columnist for Voice of the Chechen Republic, a newspaper that was really the voice of the Parliament of the first convocation of the Chechen Republic. After the Parliament dispersed in 1993, she worked for some time in Moscow in the Federal Ministry for Nationalities and traveled repeatedly to Grozny during the period of hostilities.

In Soviet times, M. Katysheva’s essays on people of an interesting fate were included in collections published by the Chechen-Ingush book publishing house, and her poems were published in the collective poetry collections “Time runs,” “a meeting on the road,” “Lyrica-90.” In the mid-1990s, she participated in the realization of the literary project “Celebrated Chechens” by writer Musa Geshaev. She is also the author-compiler of the four-volume documentary and journalistic book “Chechen lessons” (collection of materials for 1988-1999, to date only the first book has been published). Based on the results of the work for 1990, M. Katysheva was recognized as journalist of the year and received the first Aslanbek Sheripov award. In 1994, by a decision of a special commission approved by the government of the Chechen Republic, she was stats presented for the award “for merit to the people.”