THE ORIGINS – THE NATIONAL GUARD

The first armed group formed by Chechen was recruited from the security forces of the Executive Committee of the Chechen National Congress (Ispolkom) in the aftermath of the “August Putsch” orchestrated by Soviet conservatives against Mikhail Gorbachev. While the entire USSR was in turmoil and the leadership of the Chechen-Ingush ASSR was locked in a guilty silence, Dzhokhar Dudaev and the leaders of the Congress armed four platoons of volunteers and formed the National Guard. It was an irregular force with makeshift equipment, headed by three Afghanistan veterans and a young activist with a rather turbulent past, Shamil Basayev, who was destined to become one of the “champions” of Chechen independence.

The newly formed National Guard numbered between 100 and 150 volunteers, but only a few of them were actually armed: at the end of August, Bislan Gantemirov, the member of the Executive Committee responsible for the “Defense Commission,” managed to obtain a shipment of light weapons and grenades purchased from an unknown source. With this small arsenal, the Congress militiamen took control of several government offices and set up firing positions throughout the city. On September 6, a commando unit under Basayev’s command managed to penetrate the KGB building, which was poorly guarded at the time. His men took control of the building, first getting their hands on a small armory, then on a huge underground weapons depot, with which they were able to arm hundreds of volunteers. The National Guard further swelled its ranks, reaching six platoons and effectively taking control of Grozny. The regular army and militia under the orders of the Chechen Ministry of the Interior did not intervene, either in solidarity with the rebels or because they did not oppose them, so that by the end of October 1991, the legitimate government of Doku Zavgaev was overthrown and forced into exile. On October 27, popular elections were held, leading to the establishment of the first independence parliament and the appointment of Dudaev as President of the Republic. (For further information, read “Freedom or Death: History of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria,” available for purchase HERE).

The newly formed Parliament immediately attempted to give the National Guard an institutional status, officially establishing the corps and entrusting its training to Soviet army officer Magomed Shamayev, but the measure was “overturned” by a decree issued by Dudaev on November 2, which established the Ministry of War, and then by a decree issued on November 16, whereby Dudaev placed himself in command of all armed groups operating in Chechnya. He then established an army headquarters and appointed Red Army Lieutenant General Viskhan Shakhabov as Chief of Staff. His idea was to establish a professional force of 7,000 men. The army would be organized into six departments: the National Guard would be the main fighting unit. The Border Guard would guard the republic’s borders, while the “internal troops” would serve as a militia at the disposal of the Ministry of the Interior. The Special Forces would have been the army’s special units, and among these, the Presidential Guard was established, responsible for defending the President, his family, and government structures. Movlad Dzhabrailov, karate master and Dudaev’s personal trainer, was appointed to command it. The labor service and the reserve would have constituted the critical mass that could be mobilized immediately in the event of war. By a special decree of December 24, 1991 (“Law on the Defense of the Republic”), all citizens between the ages of 18 and 26 were called up for military service for a year and a half for those without a high school diploma and one year for educated citizens. The volunteer units that had formed the National Guard were essentially left to their own devices. Many returned to their homes or joined the “official” units that were being formed. Others followed the only remaining platoon commander, Shamil Basayev, and took up quarters in a sports complex on the outskirts of Grozny, where he continued to train them, assisted by another volunteer from the early days, Umalt Dashayev.

THE “ABKHAZIAN BATTALION”

At the beginning of January, it became clear that Dudaev had no intention of employing Basayev and his men. So the young commander of the National Guard decided to put himself at the service of the Confederation of Caucasian Peoples, a pan-Caucasian irredentist organization that at that time supported the cause of Abkhazia, a small region claiming full independence from Georgia. Basayev and Dashayev took command of a volunteer contingent to support the Abkhaz guerrillas in their struggle for independence. They were joined by Ruslan Gelayev, another young nationalist eager to fight. During 1992, two “international brigades,” composed largely of Chechens, crossed the Caucasus, forcing their way through the weak checkpoints set up by the federal army, and fought relentlessly (and mercilessly) against the Georgians. Basayev was appointed Deputy Minister of Defense by the Abkhaz separatist government, such was his contribution to the Abkhaz cause.

Between 1992 and 1993, the international brigades fought alongside the Abkhaz militias and were instrumental in the recapture of Gagra and Sukhumi and the liberation of the separatist garrison barricaded in Tvarcheli. Basayev’s men fought boldly, earning a reputation as fearsome soldiers. Some of them did not shy away from acts of genuine cruelty during the ethnic cleansing that followed Abkhazia’s secession from Georgia. Upon its return to Chechnya in October 1993, the so-called “Abkhaz Battalion” was considered the best fighting unit in the Caucasus, and Basayev was already a legend among nationalists.

THE REGULAR ARMY FROM THE REVOLUTION TO JUNE 4, 1993

While Basayev, Gelayev, and Dashayev were in Abkhazia, Dudaev tried to put together a regular army. On December 24, 1991, the Chechen government had instituted compulsory military conscription, and on February 17, 1992, Dudaev decreed amnesty for all soldiers in the Russian army who intended to enlist in the ranks of the new Chechen army. In the following months, many non-commissioned officers, some of whom were veterans of Afghanistan, placed themselves at the disposal of the new General Staff. In June 1992, the Russian garrisons still stationed in Chechnya withdrew definitively, leaving most of their military equipment in Chechen hands. Dudaev was able to get his hands on a huge arsenal consisting not only of tens of thousands of small arms, but also heavy weapons, grenades, armored vehicles, and even warplanes, as well as a large quantity of ammunition.

With these resources at its disposal, the Chechen government began to arm its first regular units. The first contingent was established at the end of 1991 and was called the “Presidential Guard.” It was a small fighting force totally loyal to Dudaev, responsible for his personal security and that of his family. The original core, about 20 people, was placed under the command of Movlad Dzabrailov, a black belt in karate and instructor to the president himself. In early 1992, it was decided to expand the corps to 200 units and make them the “praetorians” of the Presidency of the Republic. Letters were sent to all the villages in Chechnya, asking local councils to select the most valiant and selfless young men to serve in what was to be the elite corps of the armed forces. By the end of 1993, the corps numbered about 120 men, mostly quartered near the Presidential Palace and opposite it in the rooms of the Hotel Kavkaz. It was Dudaev’s “praetorians” who foiled an attempted coup by the so-called “opposition” to the independence government on March 31, 1992: thanks to the prompt intervention of these units, the militia armed by the “Emergency Committee” (a junta composed of former Soviet officials) was besieged in the city building in Grozny and defeated (for further information, read “Freedom or Death: History of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria,” available HERE).

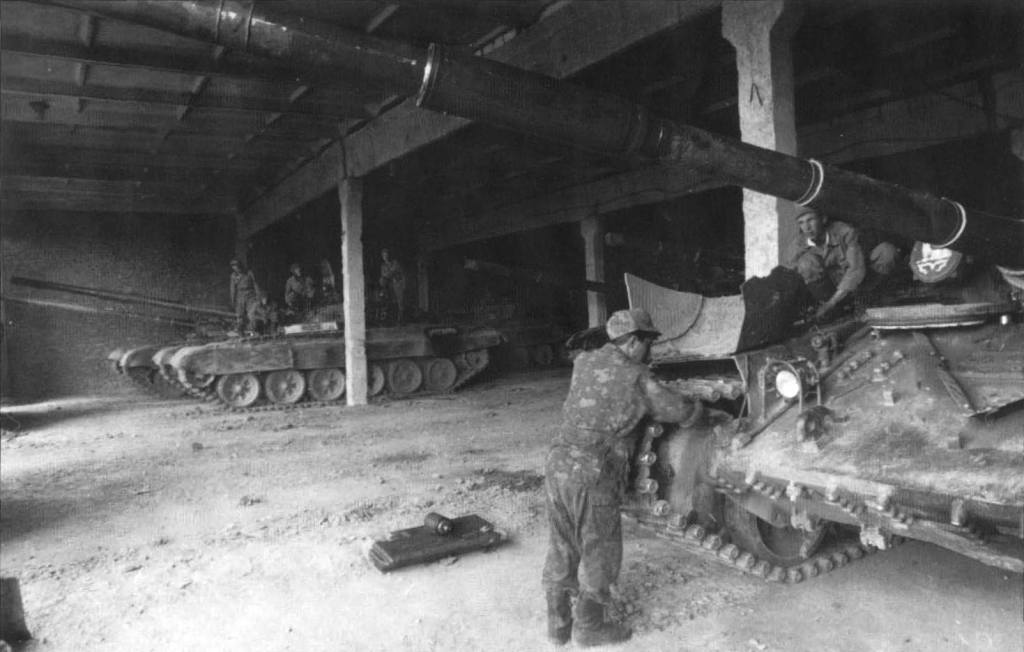

In addition to the Presidential Guard, the Chechen General Staff organized an armored regiment, putting back into service the armored vehicles and tanks abandoned by the Russians in June 1992. This gave rise to the “Shali Armored Regiment,” the backbone of the regular army, armed with T-72 and T-65 tanks and stationed in the city from which it took its name. Unlike the Presidential Guard, however, the Shali Regiment had its own policy, not always in line with Dudaev, and its commanders were reluctant to be commanded by the Grozny government. Throughout 1992 and 1993, the regiment existed only on paper, and its units pursued a policy that was almost independent of the central government.

In addition to small arms and tanks, Dudaev had also managed to get his hands on about 250 aircraft, mostly training planes, but still capable of carrying and dropping bombs. In January 1992, the Chechen government ordered the formation of the first combat air wing, which was operational by the spring. Young pilots were trained at the local training airport in Kalinovskaya, while some recruits were sent to Turkey and Pakistan.

THE COUP D’ÉTAT OF JUNE 4

When the volunteers of the “Abkhaz Battalion” returned to Chechnya, they found the country in turmoil: friction between Parliament and the President had caused an institutional crisis that had paralyzed the state. To force the situation and regain control, Dudaev staged a military coup, dissolved all democratic institutions, and established a personal dictatorship. Basayev, Gelayev, and Dashayev initially sided against him, organizing a military pronouncement in front of the Presidential Palace. However, Dudaev was able to convince them to join his ranks: each of them would form their own military unit, which would be part of the regular army and have access to the armed forces’ arsenal. In return, the three leaders would support the regime and defend it from opposition militias, which were organizing themselves into a full-fledged army financed and armed by Russia.

Thus were born Shamil Basayev’s Reconnaissance and Sabotage Battalion, Ruslan Gelayev’s ‘Borz’ (‘Wolf’) Special Forces Regiment, and Dashayev’s Separate ‘Borz’ Battalion (which later became an autonomous unit). These three units, alongside the ‘Galachozh’ Regiment (a unit formed by Dudaev in July 1993 and made up mainly of volunteers from the mountain villages of Chechnya), the “Shali” Regiment (which had meanwhile come under the command of Ruslan Alikhadzhiev, loyal to Dudaev and the independence cause) and the Presidential Guard, formed the backbone of the armed forces of the Republic of Ichkeria. There were just over a thousand men, but most of them were veterans of Afghanistan, Abkhazia, and Nagorno-Karabakh (another conflict zone where some Chechens had served shortly before the outbreak of the war of secession between Abkhazia and Georgia). Colonel Aslan Maskhadov, who succeeded Shakhabov following the coup d’état of June 4, 1993, was called upon to coordinate the actions of these corps and was officially awarded the title of Chief of Staff in March 1994.

THE CIVIL WAR

From the summer of 1994, clashes between the regime, which controlled the center and south of the country, and the opposition, which controlled the north and the province of Urus-Martan, became increasingly heated, leading to a full-scale civil war. The loyalists drove the rebels further and further into their territories: in September 1994, Maskhadov coordinated an attack against the most fierce of them, Ruslan Labazanov, once loyal to Dudaev, who had first entrenched himself in a “fortress building” in Grozny, then on the outskirts of Argun. The loyalists drove Labazanov out, and he retreated north. Dudaev’s forces then engaged the enemy at Tolstoy-Yurt, Urus-Martan, and Kalaus, but were unable to defeat them. In the meantime, they were forming a large armored detachment with the support of the federal army, which sent money, men, and sufficient resources to launch an assault on Grozny and overthrow the regime.

From October 1994, the actions of the opposition became increasingly bold, and on October 15, an armed unit managed to reach the center of the capital by surprise, then retreating without suffering heavy losses. It was a dress rehearsal for a decisive attack. On November 26, 1994, an army of more than 2,000 men supported by dozens of tanks, self-propelled howitzers, and armored vehicles penetrated the heart of the capital under the air cover provided by the Russian Air Force. The attack had been planned by Maskhadov, who deployed his units so that they could strike only once the enemy had entered the residential neighborhoods, which were occupied by multi-story reinforced concrete buildings ideal for snipers and teams armed with RPGs. As soon as the attackers had settled in the city center, the separatist army teams descended on them, decimating them and destroying most of their equipment. Within a few hours, the rebel army was scattered: many of the damaged tank crews were Russian mercenaries recruited in the previous weeks by the federal secret services, and their capture by the separatists was a major embarrassment for the Kremlin. The armed forces of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria achieved their first major victory, but it was also the first in a long series of battles that would disintegrate their unity (for more information, read “Freedom or Death: History of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria,” available HERE).

THE FIRST CHECHEN WAR

The Battle of Grozny on November 26, 1994 marked the informal beginning of the First Chechen War. Within fifteen days, the Russian government, citing the chaos that had erupted in Chechnya, ordered the army and the Minister of the Interior to end the civil war and disarm the “illegal armed groups.” This terminology was used to refer to the regular forces of the ChRI, which, as organs of a state not recognized by Moscow, were considered armed gangs.

The Russian invasion united the Chechen population around Dudaev, who was seen as the champion of national independence. Even his opponents, upon hearing news of the attack, enthusiastically sided with the separatists and asked to enlist as volunteers. Within a few days, the small contingents following Maskhadov swelled to tens of thousands. With this shock force (poorly armed, ill-equipped, but endowed with unshakeable willpower), Maskhadov was able to set up a series of defensive lines stretching from the mountains north of Grozny to the mountain gorges in the south, providing his men with shelter, supplies, and safe escape routes.

The main units we have already mentioned were all deployed in the house-to-house defense of the capital. The Presidential Guard was almost completely destroyed, but together with the volunteer units flanking it, it held back almost 15,000 federal army troops. At the end of the battle, only about 40 men survived, and only nine of them saw the end of the war. Basayev, Gelayev, and Dashayev’s men also fought to the last. Dashayev’s unit, in particular, was the protagonist of a heroic counterattack near Khankala, during which the ChRI forces engaged overwhelming enemy forces without the support of the air force (destroyed on the ground in the early days of the war) and were finally forced to retreat. During the clash, Dashayev himself was killed.

After the fall of Grozny, the Chechen army suffered a series of setbacks, mainly caused by Russian superiority in men and equipment, which proved fatal in open terrain: Chechen units were subjected to heavy air and artillery bombardment and gradually retreated towards the mountains. Here they managed to engage federal forces for five months, before the inexorable advance of Moscow’s armored brigades forced them to switch to guerrilla warfare. By late spring 1995, there were no longer any organized units capable of waging conventional warfare, but rather a galaxy of small partisan bands entrenched in the mountains, from which they descended to carry out limited raids and seize military equipment from federal garrisons.

The first turning point in the conflict came between June 14 and 19, 1995, when elements of Shamil Basayev’s Reconnaissance and Sabotage Battalion took control of the town of Budennovsk, barricaded themselves in the town hospital, and negotiated a ceasefire in Chechnya. The operation, which had clear terrorist connotations, nevertheless achieved the political result Basayev had hoped for, and in the following months Russian military operations were suspended, giving the Chechens time to reorganize their units into a coherent front and plan a campaign of attacks for the following autumn. From October 1995, the separatists, still under Maskhadov’s command, harassed federal forces with daily attacks, testing the enemy’s resolve throughout the winter. In March 1996, they pushed into Grozny, organizing a demonstration raid during which they held Moscow units and collaborationist Chechen units at bay before retreating, unpunished, to their starting positions. The death of Dudaev on April 21, 1996, did not lead to the fall of the independence movement, which instead continued its actions with renewed vigor, organizing a large-scale attack on the capital in August 1996. The action, called ‘Operation Jihad’, saw the defeat of the Russians and the end of hostilities, with the signing of the Khasavyurt Accords and the withdrawal of Moscow’s troops (for further information, read ‘Libertà o Morte: storia della Repubblica Cecena di Ichkeria‘ [Freedom or Death: History of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria], available HERE).

POST-WAR CHECHNYA

At the end of the war, the Chechens were victorious, but completely devastated. The country was destroyed, the economy non-existent, and the tens of thousands of militiamen who had contributed to the victory had no other occupation that would allow them to reintegrate into society. Maskhadov, elected President of the Republic in January 1997, attempted to reorganize the state, but found himself hostage to his own field commanders, who did not demobilize their units and used them as a political pressure tool to keep the country in anarchy and, at times, to satisfy their thirst for power. Maskhadov reorganized the army into a small professional force, the National Guard, organized into three battalions: the First, dedicated to Dudaev, the Second, named after Dashayev, and the Third, named after another “champion” of Chechen independence, Khamzat Khankarov. Basayev and Gelayev remained in arms with their militias, flanked by another forty or so “Brigade Generals” (a rank recognized both during and after the war to almost all commanders of an armed gang), who used their units as personal militias, sometimes loyal to the government, sometimes its opponents.

In 1998, the explosive situation in the Republic, made even more unstable by the conversion of many of the field commanders to Islamic fundamentalism, erupted into a new creeping civil war, which sometimes exploded into full-scale battles, such as the one in Gudermes in July 1998. The impossibility of bringing the military leaders of the ChRI to heel and the fear of triggering a second civil war forced Maskhadov to come to terms with the leaders of radical nationalism (Basayev and Gelayev in particular) and accept the gradual Islamization of the state. Bolstered by substantial impunity, Islamist leaders organized a massive raid in Dagestan in the summer of 1999, with the aim of exporting the anti-Russian insurgency and setting the entire Caucasus ablaze. Moscow’s response was swift, and in the fall of that year, federal forces invaded Chechnya again, bombing it into submission.

THE SECOND CHECHEN WAR

This time, the ChRI forces were “regular” only on paper. Very little remained of the units organized before the conflict: the Presidential Guard, reconstituted under Maskhadov, was a small core of young recruits, and the newly formed National Guard did not have the potential to offer professional defense against the invasion. The main forces were made up of the old militias of the field commanders who, with the outbreak of hostilities, largely formed a united front with the government. However, some field commanders decided to support Russia and distance themselves from separatism: brigadier generals of some importance, such as Ruslan Yamadaev, and political and religious leaders, such as Akhmat Kadyrov, dissociated themselves from the separatist cause, citing their opposition to the Islamist drift it had taken. Their militias placed themselves at the service of the federal troops, forming the backbone of the army loyal to Moscow (a role they still hold today).

Once again, Maskhadov organized the defense, basing it in Grozny, a “concrete jungle” where the Russians’ technological and numerical superiority would be severely compromised. The defense of the city was entrusted to Aslambek Ismailov, another of the brigadier generals who had won the First Chechen War. All the “illustrious” Chechen military commanders worked alongside him: Gelayev, Basayev, but also Israpilov, Lecha Dudaev, etc. The battle raged from the end of December 1999 to mid-February 2000, and most of the commanders who had made up the old Chechen army were killed during the fighting.

Some managed to escape death in a dramatic retreat that led them and their men to the Argun Gorge, the last separatist stronghold in open terrain. Basayev himself, who survived the battle and the retreat, arrived in the gorge seriously wounded, having lost a foot to a landmine. In March 2000, the separatist stronghold of Argun was stormed, and the last two large units of the ChRI army, commanded by Gelayev and the Arab Ibn Al Khattab, attempted a sortie from the valley. Both groups managed to escape the federal siege, but at a considerable cost: Gelayev’s units were involved in a dramatic battle at Komsomolskoye on March 26, 2000, and were largely destroyed. Gelayev managed to escape with a few hundred men, crossing the border with Georgia and distancing himself from the conflict until 2002. Khattab’s units managed to break through the federal ring and disperse in southeastern Chechnya, but they lost their ability to carry out large-scale actions (for more information, read “Freedom or Death: History of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria,” available HERE).

In the years that followed, the separatists waged a grueling guerrilla war, engaging tens of thousands of Russian soldiers and alternating guerrilla tactics with outright terrorist actions. The main architect of the policy of terror was Basayev, author of the Budennovsk raid during the First Chechen War, who continued to argue until the end that “bringing the war to Russia” was the only way to end it. The original “regular” army units, meanwhile, reorganized themselves into “Jamaat,” or “communities.” With no stable front and no secular state to defend, the majority of Chechen guerrillas began to see themselves as part of an army of religious fighters. Fundamentalism pervaded the ethics and rhetoric of the fighters, who gradually became disaffected with the nationalist ideal and embraced that of Islamic insurrection. After Maskhadov’s death on March 8, 2005, power passed to his successor, Abdul Halim Sadulayev, an Islamic student and supporter of the transformation of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria into an Islamic emirate. Under him, the Chechen armed forces merged with Islamic armed groups active throughout the Caucasus, forming an armed force called the Caucasus Front. This was the beginning of the end for the ChRI army. After Sadulayev’s death, on June 16, 2006, power was transferred to his “Naib” (successor) Doku Umarov, who definitively transformed the ChRI into a province (Vaylat) of the Emirate of the Northern Caucasus, of which he proclaimed himself Emir. From that moment on, the armed forces of the ChRI ceased to exist even virtually.